After receiving an experimental treatment to stop the body from attacking itself, five people no longer have any symptoms of lupus.

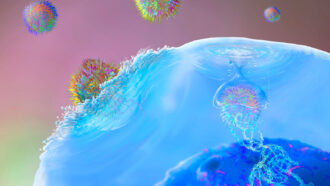

That treatment, called CAR-T cell therapy, seems to have reset the patients’ immune systems, sending their autoimmune disease into remission, researchers report September 15 in Nature Medicine. It’s not yet clear how long the relief will last or whether the therapy will work for all patients.

Even so, the results could be “revolutionary,” says immunologist Linrong Lu of the Shanghai Immune Therapy Institute at the Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, who was not involved in the study. CAR-T cell therapy has been used for various types of cancer, but it’s still in testing for autoimmune diseases (SN: 2/2/22).

In the new study, all five participants went into remission without needing additional drugs beyond the genetically engineered CAR-T cells. The target of those engineered cells — immune cells key for fighting off infections — returned a few months after being wiped out. Some of those cells are primed to attack viruses and bacteria but not the study participants’ healthy cells.

It’s unknown how many people worldwide have lupus, a painful disease in which some immune proteins called antibodies attack healthy tissue and organs (SN: 4/25/19). An estimated 161,000 to 322,000 people in the United States live with the most common form called systemic lupus erythematosus. While there are effective therapies, those treatments don’t work for everyone.

The five people in the study had this common form with symptoms resistant to multiple commonly used lupus drugs, such as hydroxychloroquine. But laboratory studies in mice hinted that CAR-T cells might help. So immunologist Georg Schett and colleagues took T cells from each patient and genetically modified the cells to track down and kill all antibody-producing cells. All five participants — four female and one male ages 18 to 24 — were in remission three months after being treated with the altered cells.

The antibody-producing cells, called B cells, disappeared from blood samples as the CAR-T cells killed them off. But B cells are an important defense against infectious diseases such as measles. Luckily, the immune cells weren’t gone permanently, says Schett, of Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg in Germany. A few months later, the patients’ bone marrow had made more. The B cells were back; the lupus was not.

“Which means, in a way, that we have a reset of the immune system in these young individuals,” Schett says.

Typically, the immune system has checkpoints that eliminate cells that attack the body instead of a foreign invader. Autoimmune diseases such as lupus occur when these cells that recognize and attack “self” escape scrutiny. For lupus to come back, Schett says, the same mistake may need to happen twice. “So far we think the disease is gone.”

To know for sure, the team needs more time to follow the participants. In August 2021, the researchers reported in the New England Journal of Medicine that the first treated participant, a 20-year-old woman, was in remission three months after receiving the drug. Now, that patient has been healthy for a year and a half, Schett says. The other four have been healthy for six months to a year. Time will tell how long these people will stay lupus-free.

Which people might benefit most from CAR-T cell therapy is not yet clear either. Lupus symptoms and severity vary from person to person. The treatment could, for instance, be most useful for patients who are in earlier stages of the disease before it becomes too severe, Lu says. Still, if future clinical trials prove effective, CAR-T cell therapy could be another way to offer hope to patients with the disease.

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes  What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?

What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?  This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces

This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces  Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now

Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now  Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight

Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight  A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?

A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?