YANGON: Thousands of people at the world’s largest jade mining site in northernmost Myanmar are turning to a hazardous illegal search for the precious stone after coronavirus bans stopped official production.

Mining activity in Hpakant, in Kachin State — the center of Myanmar’s lucrative jade trade — came to a standstill for three monsoon months after a landslide killed 172 people on July 2.

The ban has since been extended beyond the monsoon break with the worsening coronavirus outbreak, prompting more people to enter the site illegally.

“Jade mining is lifeblood of Hpakant,” Tint Soe, a lawmaker representing the town of 300,000 people, told Arab News earlier this week. “The district of Hpakant houses about 40,000 migrant workers, most of them live from hand to mouth. Small-scale illegal mining is therefore thriving.”

Local reports show that accidents are also on the rise. Tint Soe said that at least one fatal landslide has been recorded every week since the ban.

Kyaw Naing, a miner who migrated to Hpakant from central Mgagway region three years ago, said he had no choice but to continue returning to the site illegally although he was more than aware of the danger.

He witnessed the July tragedy that killed four of his colleagues. “They were buried in waves of mud after a dam of mining waste collapsed,” he said. “We dig for jade remnants throughout the year because we rely on it to eke out a living.”

But no matter how much they dig, it will never be enough. They are allowed to take home only small stones. Big pieces go to their company or boss.

“The big stones are for government and ethnic armed organizations, while we are allowed only to take jade remnants we found,” Kyaw Naing said.

The sector has been dominated by a network companies run by the Myanmar military and the rebel Kachin Independence Army (KIA), since 1994, when they agreed on a cease-fire and divided control over the state.

The most recent report of the sector was published in 2015 by Global Witness, an international NGO that investigates natural resource exploitation, corruption and human rights abuses.

It estimated that in 2014, the jade industry in Myanmar was worth $31 billion — nearly half of the country’s gross domestic product.

The industry is fueled by demand in China, where jade has for millennia been seen a particularly special stone of both cultural and ritual importance.

With little transparency as to how mining companies operate, families of those who work for them are unlikely to receive any compensation if a relative dies. According to Tint Soe, the pandemic has become a “catalyst” and “opportunity” for the government to reform of the murky sector.

With the ban in place and no permit renewals unless companies follow the new mining law strictly, authorities are seeking a grip on the unregulated industry.

“Most of the jade mining permits will expire before next year’s monsoon,” said Than Zaw Oo, a spokesman for state-owned Myanmar Gems Enterprise, which oversees the mining industry.

“We don’t know if the companies would be able to mine jade this season even if the suspension was lifted at the end of January,” he said, explaining that mining companies require up to three months (October-December) after the rainy season to prepare for operations.

These preparations cannot start with the coronavirus ban in place.

In another move to bring more transparency, Myanmar President Win Myint last week released a directive ordering state-owned enterprises and private companies to publicize all their contracts, licensing and concession agreements.

“The directive is important because it could boost transparency. Regulating mining companies is key to the jade industry,” Tint Soe said.

“If the government manages to regulate the mining companies, things here could be better for people involved. And fatal mining incidents could also be avoided. The incidents happen mainly because of the mining companies that don’t follow the instructions in mining waste management.”

But he acknowledges that the task to rein in the “unregulated and uncontrolled” sector is not easy and it will take time to address corruption and the “broken governing system” in which mining companies are linked to military and rebel groups that control the area.

“Military and ethnic rebels have a big financial interest in the industry. So change will not come easily,” he said.

UK banks face pressure over loans to Myanmar military-linked firmsRohingya widow seeks compensation from Myanmar government

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes

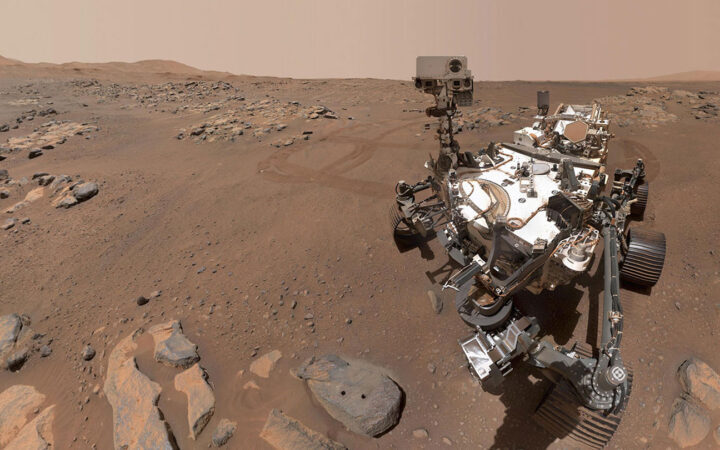

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes  What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?

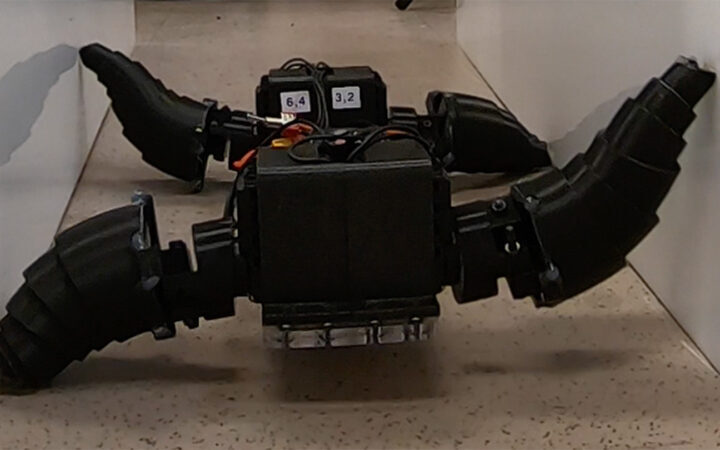

What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?  This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces

This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces  Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now

Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now  Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight

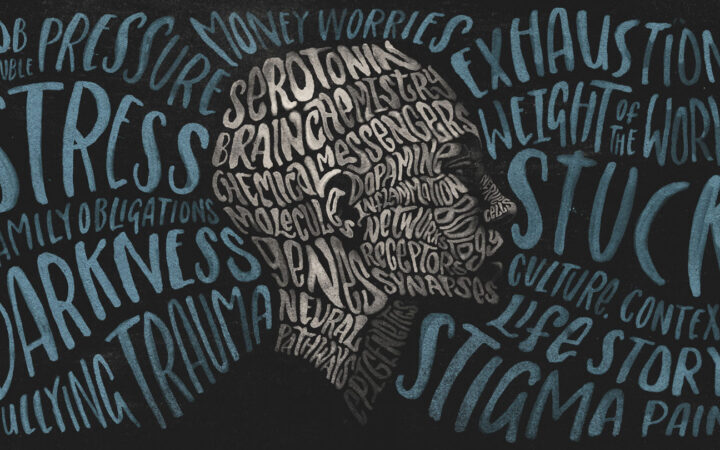

Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight  A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?

A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?