So many things launched into space this year: Six humans traveled aboard commercial crew vehicles, three spacecraft began journeys to Mars and several hundred distractingly shiny satellites took to the sky.

Commercial crew

On May 30, SpaceX ferried a pair of astronauts to the International Space Station from Cape Canaveral, Fla. It was the first human launch on a commercial spacecraft and the first time astronauts flew from a U.S. launchpad since the space shuttle was retired in 2011 (SN: 6/20/20, p. 16).

As part of its Commercial Crew Program, NASA funded private spaceflight companies, including SpaceX and Boeing, to develop ways to carry astronauts to and from the space station so the agency would no longer have to rely on the Russian Soyuz craft.

When the astronauts returned safely to Earth on August 2, the test of SpaceX’s Crew Dragon spacecraft was deemed a success. The next flight, which launched November 15, took four astronauts. “I think you can say we’re really no longer dependent on the Soyuz,” says astrophysicist and space historian Jonathan McDowell of Harvard & Smithsonian’s Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass.

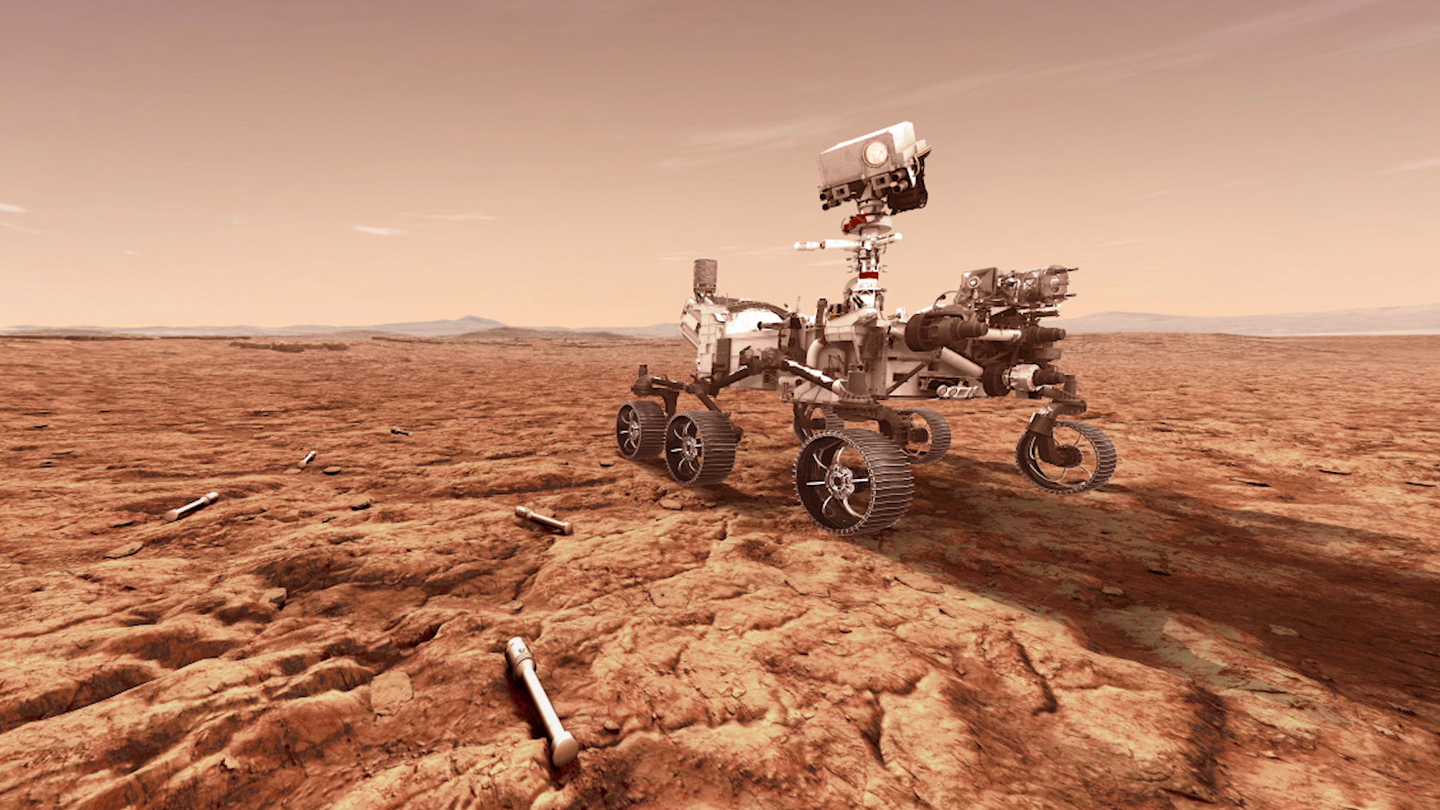

Journey to Mars

Three spacecraft that left for Mars in July are due to arrive in February 2021. The Perseverance rover, NASA’s fifth Martian rover (SN: 7/4/20 & 7/18/20, p. 30), will search a dry river delta for signs of ancient life and collect rock samples that a future mission will bring to Earth.

China and the United Arab Emirates hope this year’s missions will mark their first successful voyages to the Red Planet (SN Online: 7/30/20). After entering Mars’ orbit, China’s Tianwen-1 spacecraft is expected to drop a lander and rover onto the planet’s surface in April. China plans to bring samples back from Mars in the next decade, and Tianwen-1 is a tech demo for that mission. The rover will also look for hidden pockets of water beneath the surface and explore Mars’ geology and chemistry.

The UAE space agency was founded only in 2014 and launched its first satellite in 2018, making a Mars mission an ambitious leap. The country’s Hope orbiter will gather evidence to address one of Mars’ biggest unsolved mysteries: How does Martian weather work (SN: 7/4/20 & 7/18/20, p. 24)? By being the first spacecraft to orbit the planet’s equator, Hope will provide a new view of how Mars’ atmosphere changes daily, seasonally and at different altitudes.

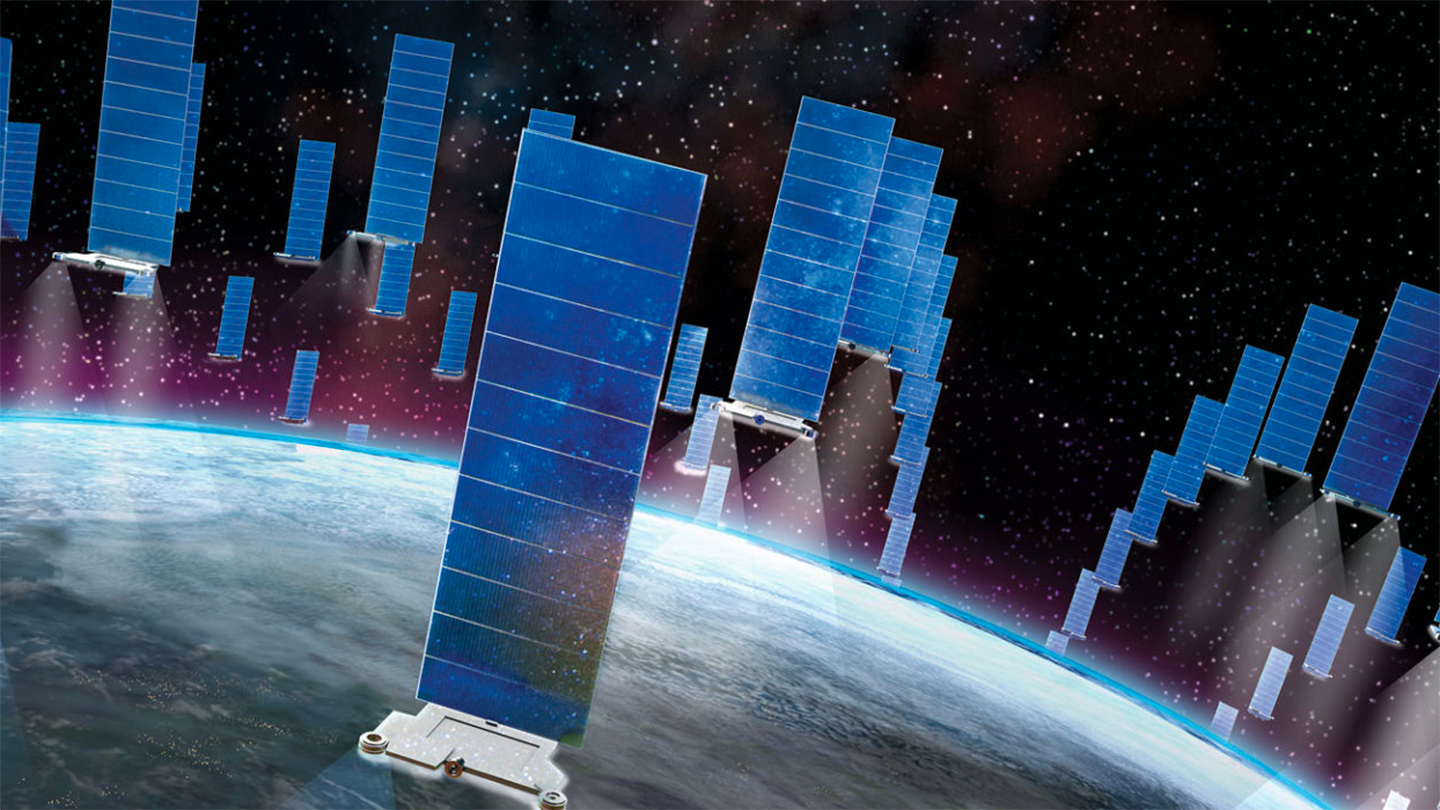

Mega-constellations

SpaceX isn’t just sending astronauts into orbit. The company has launched hundreds of satellites as part of its Starlink project to bring high-speed internet around the globe. Other companies plan to launch similar “mega-constellations.” If all goes according to various companies’ plans, there will be about 100,000 satellites in low orbits.

“That’s a lot of satellites,” McDowell says. As of August 1, just 2,787 operational satellites doing all kinds of jobs orbited the Earth. Scientists fear that the impending satellite surge could spoil the night sky for astronomy by reflecting extra light down at earthly telescopes (SN: 3/28/20, p. 24).

By mid-October, SpaceX had already launched more than 900 Starlink satellites. The company tested a dark coating meant to make the satellites less reflective, but that didn’t help enough. So now SpaceX is launching satellites with small visors to reduce reflectivity, which helps a bit, McDowell says.

The good news is that astronomers and space companies are discussing the problem. At a meeting in the summer, scientists presented simulations of the worst-case scenarios. The impact of these mega-constellations will depend on how many satellites actually launch, and what kind of astronomy you’re considering, McDowell says. Some of the worst effects will be on observations to detect near-Earth asteroids.

“We might miss the rock that’s coming to kill us all because the satellite streaks got in the way of calculating its orbit,” McDowell says.

One thing that would help is government regulations about the characteristics of satellites that can be launched, McDowell says. Companies are “making all the right noises about wanting to help,” he says, but noises and actions are not the same thing.

“I think with additional work and mitigations, we’ll get to a point where it isn’t fatal to ground-based astronomy, but it’s still a huge impact,” McDowell says. “We may not know the full consequences until we’re really in it.”

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes  What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?

What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?  This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces

This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces  Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now

Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now  Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight

Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight  A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?

A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?