Thumb dexterity similar to that of people today already existed around 2 million years ago, possibly in some of the earliest members of our own genus Homo, a new study indicates. The finding is the oldest evidence to date of an evolutionary transition to hands with powerful grips comparable to those of human toolmakers, who didn’t appear for roughly another 1.7 million years.

Thumbs that enabled a forceful grip and improved the ability to manipulate objects gave ancient Homo or a closely related hominid line an evolutionary advantage over hominid contemporaries, says a team led by Fotios Alexandros Karakostis and Katerina Harvati. Now-extinct Australopithecus made and used stone tools but lacked humanlike thumb dexterity, thus limiting its toolmaking capacity, the paleoanthropologists, from Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen in Germany, found.

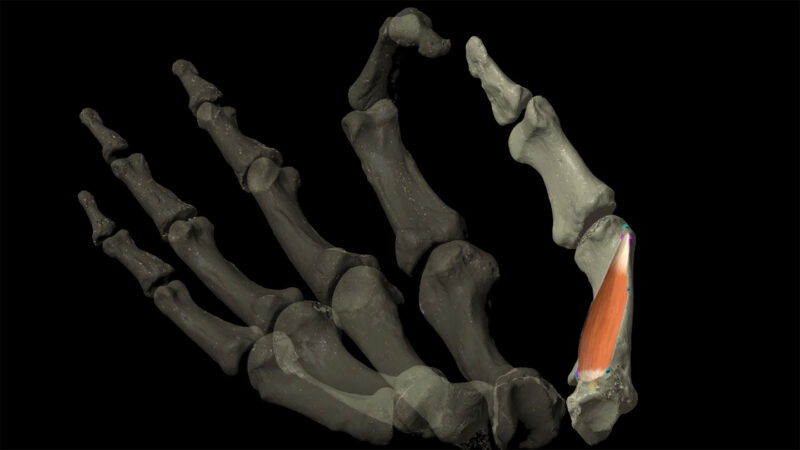

The researchers digitally simulated how a key muscle influenced thumb movement in 12 previously found fossil hominids, five 19th century humans and five chimpanzees. Surprisingly, Harvati says, a pair of roughly 2-million-year-old thumb fossils from South Africa display agility and power on a par with modern human thumbs.

Scientists disagree about whether the South African finds come from early Homo or Paranthropus robustus, a species on a dead-end branch of hominid evolution (SN: 4/2/20). But the thumb dexterity in those ancient fossils is comparable to that found in members of Homo species that appeared after around 335,000 years ago, the researchers report January 28 in Current Biology. That includes Neandertals from Europe and the Middle East, and a South African hominid dubbed Homo naledi, which possessed an unusual mix of skeletal traits (SN: 5/9/17).

By comparison, they conclude, Homo or P. robustus possessed thumbs that were more forceful than those of three several-million-year-old Australopithecus species, two of which have previously been proposed to have humanlike hands (SN: 1/22/15).

“Australopithecus would probably be able to perform most [tool-related] hand movements, but not as efficiently as humans or other Homo species we studied,” Harvati says. The tool-wielding repertoire of Australopithecus species fell closer to that of modern chimpanzees, who use twigs to collect termites and rocks to crack nuts, she suggests (SN: 11/6/09).

Harvati’s team went beyond past efforts that focused only on the size and shape of ancient hominids’ hand bones. Using data from humans and chimpanzees on how hand muscles and bones interact while moving, the researchers constructed a digital, 3-D model to re-create how a key thumb muscle — musculus opponens pollicis — attached to a bone at the base of the thumb and operated to bend the digit’s joint toward the palm and fingers.

These new models of how ancient thumbs worked underscore the slowness of hominid hand evolution, says paleoanthropologist Matthew Tocheri of Lakehead University in Thunder Bay, Canada. Australopithecus made and used stone tools as early as around 3.3 million years ago (SN: 5/20/15). “But we don’t see major changes to the thumb until around 2 million years ago, soon after which stone artifacts become far more common across the African landscape,” he says.

Karakostis and Harvati’s 3-D models of ancient thumb dexterity represent a promising advance, says paleoanthropologist Carol Ward of the University of Missouri in Columbia. But further work needs to examine how other thumb muscles interacted with musculus opponens pollicis to influence how that digit worked in different hominid species, she adds.

In a related finding, Ward and her colleagues — including Tocheri — reported in 2014 that a roughly 1.42-million-year-old hominid finger fossil from East Africa pointed to an early emergence of humanlike manipulation skills.

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes  What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?

What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?  This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces

This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces  Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now

Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now  Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight

Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight  A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?

A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?