All eyes are on Mars — and all ears, too. When NASA’s Perseverance rover touches down on the Red Planet on February 18, the landing will be recorded with sight, sound and maybe even touch.

The rover will cap off a month of Mars arrivals from space agencies around the world (SN: 7/30/20). Perseverance joins Hope, the first interplanetary mission from the United Arab Emirates, which successfully entered Mars orbit on February 9; and Tianwen-1, China’s first Mars mission, which arrived on February 10 and will deploy a rover to the Martian surface in May.

NASA will broadcast Perseverance’s landing on YouTube starting at 2:15 p.m. EST. The actual moment of touchdown is expected at approximately 3:55 p.m. EST. Perseverance is designed to explore an ancient river delta called Jezero crater, searching for signs of ancient life and collecting rocks for a future mission to return to Earth (SN: 7/28/20).

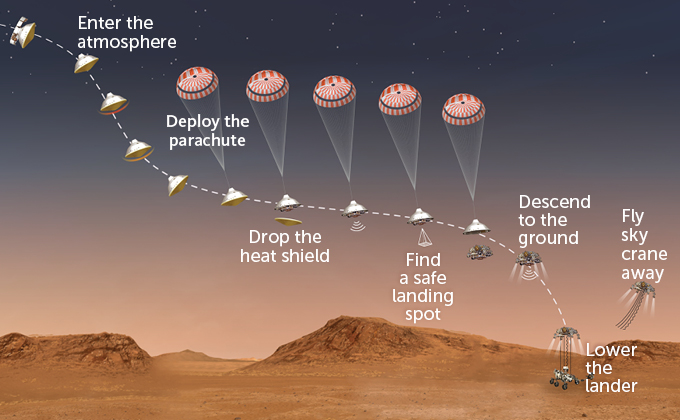

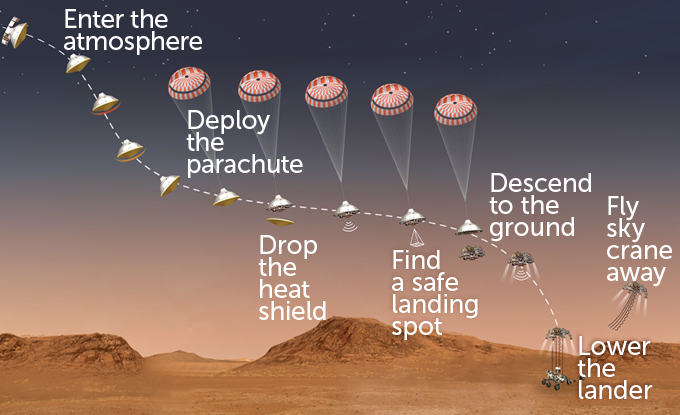

The rover will use the landing system pioneered by its predecessor, Curiosity, which has been exploring Mars since 2012 (SN: 8/6/12). But in a first for Mars touchdowns, this rover will record its own landing with dedicated cameras and a microphone.

As the craft carrying Perseverance zooms through the thin Martian atmosphere, three cameras will look up at the parachute slowing it down from supersonic speeds. When a rocket-powered “sky crane” platform lowers the rover to the ground, a fourth camera on the platform will record the rover’s descent. Another camera on the rover will look back up at the platform, and a sixth camera will look at the ground.

“The goal is to see the video and the action of getting from high up in the atmosphere down to the surface,” says engineer David Gruel of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, who was the engineering lead for that six-camera system, called EDL-Cam. He hopes every engineer on the team has an image of the rover hanging below the descent stage as their computer desktop background six months from now.

Because it will take more than 11 minutes for signals to travel between Earth and Mars, the cameras won’t stream the landing movie in real time. And after Perseverance lands, engineers will be focused on making sure the rover is healthy and able to collect science data, so the landing videos won’t be among the first data sent back. Gruel expects to be able to share what the rover saw four days after landing, on February 22.

Perseverance will also carry microphones to record first-ever audio of a Mars landing. Unlike the landing cameras, the microphones will continue to work after touchdown, hopefully helping the engineering team keep track of the rover’s health. Motors sound different when they get clogged with dust, for instance, Gruel says. The team will hear the sound of the rover’s wheels crunching across the Martian surface, and maybe the sound of the wind blowing.

“Are we going to hear a dust devil? What might a dust devil sound like? Could we hear rocks rolling down a hill?” Gruel asks. “You never know what we might stumble onto.”

Sound will add a way to share Mars with people who have trouble seeing, Gruel notes. “It might appeal to a whole other element of the population who might not have been able to experience past missions the same way,” he says.

Elsewhere on Mars, the InSight lander will be listening to the landing too (SN: 2/24/20). The lander’s seismometer may be able to feel vibrations when two tungsten weights that Perseverance carried to Mars for stability smack into the ground before the rover lands, geophysicist Benjamin Fernando of the University of Oxford and colleagues report in a paper posted December 3 to eartharxiv.org and submitted to JGR Planets.

“No one’s ever tried to do this before,” Fernando says.

The ground will move by at most 0.1 nanometers per second, Fernando and colleagues calculated. “It’s incredibly small,” he says. “But the seismometer is also incredibly sensitive.”

The team may be able to catch that tiny signal because they know exactly when and where the impact will happen. If the lander does pick up the signal, it will tell scientists something about how fast seismic waves travel through the ground, a clue to the details of Mars’ interior structure. And even if they don’t feel anything, that will put limits on the waves’ speed. “It still teaches us something,” Fernando says.

The InSight team hopes to also feel vibrations from Tianwen-1 when its rover touches down in May. “Detecting one would be great,” Fernando says. “Detecting two would be like, amazing.”

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes  What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?

What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?  This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces

This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces  Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now

Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now  Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight

Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight  A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?

A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?