The fastest punches in the animal kingdom probably belong to mantis shrimp — and they may begin unleashing these attacks a little more than a week after hatching, when they have just started to hunt prey, a new study shows.

For the first time, researchers have peered through the transparent exoskeletons of these young mantis shrimp to see the inner mechanisms of their powerful weapons in motion, researchers report online April 29 in the Journal of Experimental Biology. The findings are letting scientists in on hidden details of how these speedy armaments work.

Mantis shrimp are equipped with special pairs of arms that can explode with bulletlike accelerations to strike at speeds of up to roughly 110 kilometers per hour. Previously, scientists deduced these weapons act much like crossbows. As a latch holds each arm in place, muscles within the arm contract, storing energy within the arm’s hinge. When the crustaceans release these latches, all this energy discharges at once (SN: 8/8/19).

But researchers didn’t know at what age mantis shrimp first begin launching these spring-loaded attacks. Computer simulations predicted that the armaments might be capable of greater accelerations the smaller they got, suggesting young mantis shrimp could actually have faster weapons than adults, says Jacob Harrison, a marine biologist at Duke University.

To solve this mystery, Harrison and his colleagues collected a host of microscopic creatures off boat docks in Oahu, Hawaii, sifting out larvae of Philippine mantis shrimp (Gonodactylaceus falcatus) roughly the size of rice grains. They then glued the larvae onto toothpicks to record their punches in high-speed video. The researchers also captured a clutch of eggs from the species and raised the hatchlings for 28 days to see how the anatomy of their weaponry developed over time.

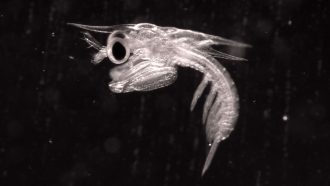

A larval mantis shrimp (Gonodactylaceus falcatus) — filmed at 2,000 frames per second and played back at 3 percent speed — retracts and locks its attack arm to store energy before releasing a strike. New research shows these larvae begin unleashing their punches by the time they are 9 days old.

As soon as nine days after hatching, the larvae began striking rapidly. Their punches flew out at speeds of about 1.4 kilometers per hour. Given their tiny arms — up to about 100 times shorter than an adult’s — that’s comparable to the speed of an adult shrimp’s punch, Harrison says. More importantly, it’s up to 10 times the swimming speeds of crustaceans and fish roughly as big as the larvae, and more than 150 times those of young brine shrimp that the researchers fed them. These weapons emerged about when the mantis shrimp larvae first begin feeding on live prey, after exhausting the yolk sacs they were born with, Harrison says.

“Mantis shrimp larvae are capable of moving incredibly quickly for something so small,” Harrison says. “It is hard for small things to move quickly — their muscles and body are so tiny, there isn’t really the time or space to build up speed.”

At 11 days old, this mantis shrimp (Gonodactylaceus falcatus) larva has already developed an appendage (folded below the eye) capable of ultrafast punches previously seen only in adults.Jacob Harrison

Mantis shrimp may need these speedy limbs when they are young “because of the water they live in,” Harrison says. Water feels more viscous for tiny creatures than it does for larger ones, so moving through it can prove challenging for microscopic larvae. However, their powerful appendages may overcome this drag to capture prey, he notes.

Contrary to what the researchers expected, the larvae were not faster than the adults. For instance, during punches, the larvae swiveled their arms at speeds roughly a third to half those of adult peacock mantis shrimp. These findings suggest there may be some constraints on these weapons at these microscopic sizes that further research can uncover, Harrison says.

Alternatively, the larvae may simply not require weapons faster than those of adults — “they just need a crossbow that works, and don’t need it to be this crazy superpowerful thing,” says invertebrate neuroecologist Kate Feller at Union College in Schenectady, N.Y., who did not take part in this research.

The most amazing part of this work, Harrison says, was how he and his colleagues could peer inside the glassy bodies of the larvae to watch how the muscles behaved during a punch, something previously only imagined from surgical dissections and CT scans.

“The fact these larvae are transparent is a great opportunity to answer questions like how the latch works,” Feller says. “That’s very exciting.”

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes  What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?

What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?  This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces

This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces  Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now

Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now  Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight

Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight  A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?

A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?