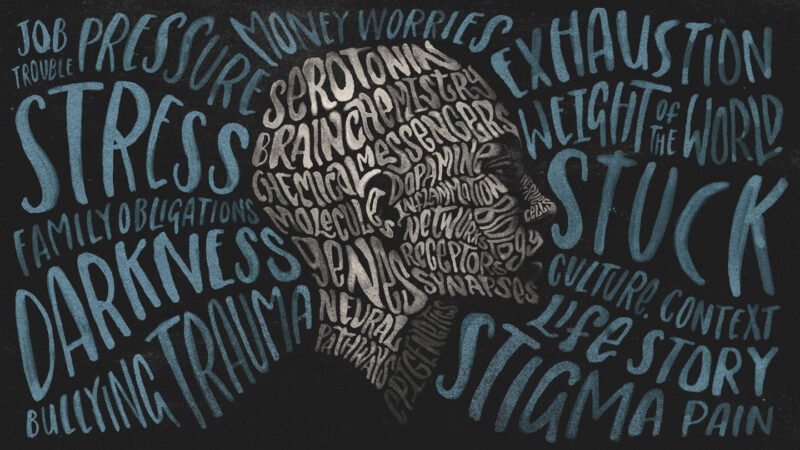

You’d be forgiven for thinking that depression has a simple explanation.

The same mantra — that the mood disorder comes from a chemical imbalance in the brain — is repeated in doctors’ offices, medical textbooks and pharmaceutical advertisements. Those ads tell us that depression can be eased by tweaking the chemicals that are off-kilter in the brain. The only problem — and it’s a big one — is that this explanation isn’t true.

The phrase “chemical imbalance” is too vague to be true or false; it doesn’t mean much of anything when it comes to the brain and all its complexity. Serotonin, the chemical messenger often tied to depression, is not the one key thing that explains depression. The same goes for other brain chemicals.

The hard truth is that despite decades of sophisticated research, we still don’t understand what depression is. There are no clear descriptions of it, and no obvious signs of it in the brain or blood.

The reasons we’re in this position are as complex as the disease itself. Commonly used measures of depression, created decades ago, neglect some important symptoms and overemphasize others, particularly among certain groups of people. Even if depression could be measured perfectly, the disorder exists amid myriad levels of complexity, from biological confluences of minuscule molecules in the brain all the way out to the influences of the world at large. Countless combinations of genetics, personality, history and life circumstances may all conspire to create the disorder in any one person. No wonder the science is stuck.

It’s easy to see why a simple “chemical imbalance” explanation holds appeal, even if it’s false, says Awais Aftab, a psychiatrist at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. What causes depression is nuanced, he says — “not something that can easily be captured in a slogan or buzzword.”

So here, up front, is your fair warning: There will be no satisfying wrap-up at the end of this story. You will not come away with a scientific explanation for depression, because one does not exist. But there is a way forward for depression researchers, Aftab says. It requires grappling with nuances, complexity and imperfect data.

Those hard examinations are under way. “There’s been some really interesting and exciting scientific and philosophical work,” Aftab says. That forward motion, however slow, gives him hope and may ultimately benefit the millions of people around the world weighed down by depression.

How is depression measured?

Many people who feel depressed go into a doctor’s office and get assessed with a checklist. “Yes” to trouble sleeping, “yes” to weight loss and “yes” to a depressed mood would all yield points that get tallied into a cumulative score. A high enough score may get someone a diagnosis. The process seems straightforward. But it’s not. “Even basic issues regarding measurement of depression are actually still quite open for debate,” Aftab says.

That’s why there are dozens of methods to assess depression, including the standard description set by the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM-5. This manual is meant to standardize categories of illness.

Variety in measurement is a real problem for the field and points to the lack of understanding of the disease itself, says Eiko Fried, a clinical psychologist at Leiden University in the Netherlands. Current ways of measuring depression “leave you with a really impoverished, tiny look,” Fried says.

Scales can miss important symptoms, leaving people out. “Mental pain,” for instance, was described by patients with depression and their caregivers as an important feature of the illness, researchers reported in 2020 in Lancet Psychiatry. Yet the term doesn’t show up on standard depression measurements.

One reason for the trouble is that the experience of depression is, by its nature, deeply personal, says clinical psychologist Ioana Alina Cristea of the University of Pavia in Italy. Individual patient complaints are often the best tool for diagnosing the disorder, she says. “We can never let these elements of subjectivity go.”

In the middle of the 20th century, depression was diagnosed through subjective conversation and psychoanalysis, and considered by some to be an illness of the soul. In 1960, psychiatrist Max Hamilton attempted to course-correct toward objectivity. Working at the University of Leeds in England, he published a depression scale. Today, that scale, known by its acronyms HAM-D or HRSD, is one of the most widely used depression screening tools, often used in studies measuring depression and evaluating the promise of possible treatments.

“It’s a great scheme for a scale that was made in 1960,” Fried says. Since the HRSD was published, “we have put a man on the moon, invented the internet and created powerful computers small enough to fit in people’s pockets,” Fried and his colleagues wrote in April in Nature Reviews Psychology. Yet this 60-year-old tool remains a gold standard.

Hamilton developed his scale by observing patients who had already been diagnosed with depression. They exhibited symptoms such as weight loss and slowed speech. But those mixtures of symptoms don’t apply to everyone with depression, nor do they capture nuance in symptoms.

To spot these nuances, Fried looked at 52 depression symptoms across seven different scales for depression, including Hamilton’s scale. On average, each symptom appeared in three of the seven scales. A whopping 40 percent of the symptoms appeared in only one scale, Fried reported in 2017 in the Journal of Affective Disorders. The only specific symptom common to all seven scales? “Sad mood.”

In a study that examined depression symptoms reported by 3,703 people, Fried and Randolph Nesse, an evolutionary psychiatrist at the University of Michigan Medical School in Ann Arbor, found 1,030 unique symptom profiles. Roughly 14 percent of participants had combinations of symptoms that were not shared with anyone else, the researchers reported in 2015 in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

Before reliable thermometers, the concept of temperature was murky. How do you understand the science of hot and cold without the tools to measure it? “You don’t,” Fried says. “You make a terrible measurement, and you have a terrible theory of what it is.” Depression presents a similar challenge, he says. Without good measurements, how can you possibly diagnose depression, determine whether symptoms get better with treatments or even prevent it in the first place?

Depression differs by gender, race and culture

The story gets murkier when considering who these depression scales were made for. Symptoms differ among groups of people, making the diagnosis even less relevant for certain groups.

Behavioral researcher Leslie Adams of Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health studies depression in Black men. “It’s clear that [depression] is negatively impacting their work lives, social lives and relationships. But they’re not being diagnosed at the same rate” as other groups, she says. For instance, white people have a lifetime risk of major depression disorder of almost 18 percent; Black people’s lifetime risk is 10.4 percent, researchers reported in 2007 in JAMA Psychiatry. This discrepancy led Adams to ask: “Could there be a problem with diagnostic tools?”

Turns out, there is. Black men with depression have several characteristics that common scales miss, such as feelings of internal conflict, not communicating with others and feeling the burdens of societal pressure, Adams and colleagues reported in 2021 in BMC Public Health. A lot of depression measurements are based on questions that don’t capture these symptoms, Adams says. “ ‘Are you very sad?’ ‘Are you crying?’ Some people do not emote in the same way,” she says. “You may be missing things.”

American Indian women living in the Southeast United States also experience symptoms that aren’t adequately caught by the scales, Adams and her team found in a separate study. These women also reported experiences that do not necessarily signal depression for them but generally do for wider populations.

On common scales, “there are some items that really do not capture the experience of depression for these groups,” Adams says. For instance, a common question asks how well someone agrees with the sentence: “I felt everything I did was an effort.” That “can mean a lot of things, and it’s not necessarily tied to depression,” Adams says. The same goes for items such as, “People dislike me.” A person of color faced with racism and marginalization might agree with that, regardless of depression, she says.

Our ways to measure depression capture only a tiny slice of the big picture. The same can be said about our understanding of what’s happening in the brain.

The flawed serotonin hypothesis

Serotonin came into the spotlight in part because of the serendipitous discovery of drugs that affected serotonin receptors, called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SSRIs. After getting its start in the late 1960s, the “serotonin hypothesis” flourished in the late ’90s, as advertisers ran commercials that told viewers that SSRIs fixed the serotonin deficit that can accompany depression. These messages changed the way people talked and thought about depression. Having a simple biological explanation helped some people and their doctors, in part by easing the shame some people felt for not being able to snap out of it on their own. It gave doctors ways to talk with people about the mood disorder.

But it was a simplified picture. A recent review of evidence, published in July in Molecular Psychiatry, finds no consistent data supporting the idea that low serotonin causes depression. Some headlines declared that the study was a grand takedown of the serotonin hypothesis. To depression researchers, the findings weren’t a surprise. Many had already realized this simple description wasn’t helpful.

There’s plenty of data suggesting that serotonin, and other chemical messengers such as dopamine and norepinephrine, are somehow involved in depression, including a study by neuropharmacologist Gitte Moos Knudsen of the University of Copenhagen. She and colleagues recently found that 17 people who were in the midst of a depressive episode released, on average, less serotonin in certain brain areas than 20 people who weren’t depressed. The study is small, but it’s one of the first to look at serotonin release in living human brains of people with depression.

But Knudsen cautions that those results, published in October in Biological Psychiatry, don’t mean that depression is fully caused by low serotonin levels. “It’s easy to defer to simple explanations,” she says.

SSRIs essentially form a molecular blockade, stopping serotonin from being reabsorbed into nerve cells and keeping the levels high between the cells. Those high levels are thought to influence nerve cell activity in ways that help people feel better.

Because the drugs can ease symptoms in about half of people with depression, it seemed to make sense that depression was caused by problems with serotonin. But just because a treatment works by doing something doesn’t mean the disease works in the opposite way. That’s backward logic, psychiatrist Nassir Ghaemi of Tufts University School of Medicine in Boston wrote in October in a Psychology Today essay. Aspirin can ease a headache, but a headache isn’t caused by low aspirin.

“We think we have a much more nuanced picture of what depression is today,” Knudsen says. The trouble is figuring out the many details. “We need to be honest with patients, to say that we don’t know everything about this,” she says.

The brain contains seven distinct classes of receptors that sense serotonin. That’s not even accounting for sensors for other messengers such as dopamine and norepinephrine. And these receptors sit on a wide variety of nerve cells, some that send signals when they sense serotonin, some that dampen signals. And serotonin, dopamine and norepinephrine are just a few of dozens of chemicals that carry information throughout a multitude of interconnected brain circuits. This complexity is so great that it renders the phrase “chemical imbalance” meaningless.

Overly simple claims — low serotonin causes depression, or low serotonin isn’t involved — serve only to keep us stymied, Aftab says. “[It] just keeps up that unhelpful binary.”

Depression research can’t ignore the world

In the 1990s, Aftab says, depression researchers got intensely focused on the brain. “They were trying to find the broken part of the brain that causes depression.” That limited view “really hurt depression research,” Aftab says. In the last 10 years or so, “there’s a general recognition that that sort of mind-set is not going to give us the answers.”

Reducing depression to specific problems of biology in the brain didn’t work, Cristea says. “If you were a doctor 10 years ago, the dream was that the neuroscience would give us the markers. We would look at the markers and say, ‘OK. You [get] this drug. You, this kind of therapy.’ But it hasn’t happened.” Part of that, she says, is because depression is an “existentially complicated disorder” that’s tough to simplify, quantify and study in a lab.

Our friendships, our loves, our setbacks and our stress can all influence our health. Take a recent study of first-year doctors in the United States. The more these doctors worked, the higher the rate of depression, scientists reported in October in the New England Journal of Medicine. Similar trends exist for caregivers of people with dementia and health care workers who kept emergency departments open during the COVID-19 pandemic. Their high-stress experiences may have prompted depression in some way.

“Depression is linked to the state of the world — and there is no denying it,” Aftab says.

Today’s research on depression ought to be more pluralistic, Adams says. “There are so many factors at play that we can’t just rest on one solution,” she says. Research from neuroscience and genetics has helped identify brain circuits, chemical messengers, cell types, molecules and genes that all may be involved in the disorder. But researchers aren’t satisfied with that. “There is other evidence that remains unexplored,” Adams says. “With our neuroscience advances, there should be similar advances in public health and psychiatric work.”

That’s happening. For her part, Adams and colleagues have just begun a study looking at moment-to-moment stressors in the lives of Black adolescents, ages 12 to 18, as measured by cell phone questionnaires. Responses, she hopes, will yield clues about depression and risk of suicide.

Other researchers are trying to fit together all of these different ways of seeing the problem. Fried, for example, is developing new concepts of depression that acknowledge the interacting systems. You tug on one aspect of it — using an antidepressant for instance, or changing sleep patterns — and see how the rest of the system reacts.

Approaches like these recognize the complexity of the problem and aim to figure out ways to handle it. We will never have a simple explanation for depression; we are now learning that one cannot possibly exist. That may sound like cold comfort to people in depression’s grip. But seeing the challenge with clear eyes may be the thing that moves us forward.

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes  What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?

What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?  This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces

This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces  Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now

Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now  Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight

Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight  Cockatoos can tell when they need more than one tool to swipe a snack

Cockatoos can tell when they need more than one tool to swipe a snack