An individual from an enigmatic hominid species strode across a field of wet, volcanic ash in what is now East Africa around 3.66 million years ago, leaving behind a handful of footprints.

Those five ancient impressions, largely ignored since their partial excavation at Tanzania’s Laetoli site in 1976, show hallmarks of upright walking by a hominid, a new study finds. Researchers had previously considered them hard to classify, possibly produced by a young bear that took a few steps while standing.

Nearby Laetoli footprints unearthed in 1978 looked more clearly like those of hominids and have been attributed to Lucy’s species, Australopithecus afarensis (SN: 12/16/16). But the shape and positioning of the newly identified hominid footprints differ enough from A. afarensis to qualify as marks of a separate Australopithecus species, an international team reports December 1 in Nature.

“Different [hominid] species walked across this East African landscape at about the same time, each moving in different ways,” says paleoanthropologist Ellison McNutt of Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine in Athens.

The species identity of the Laetoli printmaker is unknown.

A footprint of a proposed new hominid, left, is similar in length to a cast of a nearby footprint assigned to Australopithecus afarensis, right. But the former impression displays some chimplike traits, including a relatively wide forefoot.J. DeSilva, Eli Burakian/Dartmouth CollegeA footprint of a proposed new hominid, left, is similar in length to a cast of a nearby footprint assigned to Australopithecus afarensis, right. But the former impression displays some chimplike traits, including a relatively wide forefoot.J. DeSilva, Eli Burakian/Dartmouth College

Fossil jaws dating back more than 3 million years unearthed in East Africa may come from a species dubbed A. deyiremeda that lived near Lucy’s crowd (SN: 5/27/15). But no foot fossils were found with the jaws to compare with the Laetoli finds. The 3.4-million-year-old foot fossils from an East African hominid that had grasping toes and no arch and the unusual fossil feet of 4.4-million-year-old Ardipithecus ramidus aren’t a match either (SN: 3/28/12; SN: 2/24/21). So neither of those hominids could have made the five Laetoli prints, says McNutt, who started the new investigation as a Dartmouth College graduate student supervised by paleoanthropologist Jeremy DeSilva.

Because footprints of Lucy’s species differed in some ways from the impressions uncovered two years earlier, many researchers doubted that a hominid had made the five-step trackway, some suspecting a bear instead.

The latest analysis refutes that suggestion, says paleoanthropologist Bernard Wood of George Washington University in Washington, D.C., who did not participate in the new study. “Not one, but two [hominids] left their mark at Laetoli 3.66 million years ago.”

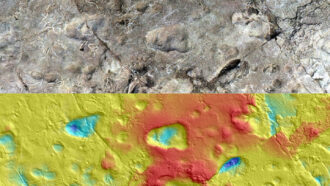

McNutt, deSilva and their colleagues fully excavated and cleaned the five Laetoli footprints in June 2019. Then they measured, photographed and 3-D scanned the ancient tracks. Print sizes indicated that they had been made by a relatively short individual, possibly one that had not yet reached maturity.

McNutt’s group focused on two consecutive footprints that were particularly well-preserved. Foot shapes, proportions and stride characteristics of the Laetoli individual differed in various ways from those of A. afarensis individuals at the same site. The prints also didn’t match those from modern juvenile black bears and modern chimps walking upright, present-day East African Daasanach people who typically don’t wear shoes or preserved footprints of East African hunter-gatherers dating to between roughly 12,000 and 10,000 years ago (SN: 5/14/20).

Ellison McNutt uses food to induce a young female black bear to walk upright across a mud patch (left). A young male bear in her study produced this footprint (right). The experiment was used to help rule out that a bear made mysterious footprints at a site in East Africa 3.66 million years ago.E.J. McNutt et al/Nature 2021

The Laetoli individual possessed a wider, more chimplike foot than A. afarensis or humans, the researchers say. Its big toe stuck out slightly from the second toe, but not to the degree observed in chimps. Signs of a balanced, upright gait in the ancient tracks resulted from humanlike knees positioned underneath the hips, humanlike hips oriented to stabilize a two-legged stride or both.

On one step, the Laetoli individual’s left leg crossed in front of the right leg, leaving a left footprint directly in front of the previous impression. People may cross-step in this way when trying to regain balance. But McNutt’s team doubts that the newly analyzed Laetoli footprints represent smudged impressions made by an A. afarensis individual that cross-stepped, perhaps to stay upright. That’s in part because footprints of Daasanach people walking as usual and then cross-stepping look largely the same, McNutt’s team found. And bears and chimps assume a relatively wide stance due to knee and hip arrangements that prevent them from walking like the Laetoli individual and probably from cross-stepping, the scientists say.

Given that only two of the ancient footprints are complete enough to analyze thoroughly, the possibility that an ape other than a hominid made the Laetoli impressions can’t be ruled out, says William Harcourt-Smith, a paleoanthropologist at Lehman College and the American Museum of Natural History in New York City who wasn’t involved in the research. But evidence of cross-stepping points to a hominid track maker, he says.

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes  What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?

What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?  This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces

This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces  Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now

Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now  Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight

Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight  A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?

A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?