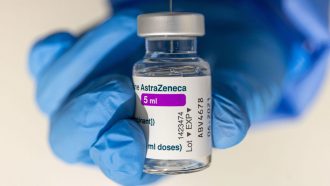

In another hiccup for AstraZeneca’s COVID-19 vaccine, data suggest it is in fact linked to blood clots that have formed in the brains of some vaccinated people, the European Medicines Agency announced April 7.

The blood clots are incredibly rare, EMA experts say. But because COVID-19 itself is deadly and can put people in the hospital, the benefits of the vaccine still outweigh the risks, they say. “We need to use the vaccines that we have to protect us from devastating effects” of COVID-19, Emer Cooke, executive director of the EMA, said in a news conference on April 7.

The EMA had previously concluded that the vaccine, developed by AstraZeneca and the University of Oxford, was not linked to blood clots overall (SN: 3/18/21). But experts were uncertain about 18 case reports of blood clots in the sinuses that drain blood from the brain, a rare condition called cerebral venous sinus thrombosis or CVST.

Enough data has now accrued to implicate the jab’s involvement in those rare blood clots, meaning CVST and similar conditions should be listed as a possible rare side effect of vaccination, the EMA’s Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee concluded after reviewing numerous cases reported in the United Kingdom and the European Union. As of March 22, countries had reported 62 cases of CVST out of around 25 million people who got the AstraZeneca vaccine. There were also 24 reported cases of clots in veins that drain blood from the digestive system, called splanchnic vein thrombosis or SVT. Eighteen of the people with CVST or SVT died.

It’s still unknown how the vaccine could cause blood clots. One potential explanation is that some people develop an immune response that attacks platelets, making them clump together, Sabine Straus, chair of the EMA committee, said in the news conference. That would make the condition similar to low platelet levels and blood clots sparked by an immune response to the anticoagulant drug heparin. One preliminary study of four people who died from blood clots after vaccination had platelet-binding antibodies in their blood, researchers reported March 29 at Research Square, a preprint server. The study has not yet been reviewed by other scientists.

If that is the way those clots form, there are ways to treat them, Beverley Hunt, a hematologist at King’s College London, said in a call with reporters. A therapy called IVIG, which contains portions of antibodies that interact with platelets, given with non-heparin anticoagulants might help break up clots.

Why the vaccine might spark clotting is also unclear. It could be related to the technology AstraZeneca used in the vaccine or something about the coronavirus protein the shot uses, Adam Finn, a pediatrician and vaccine expert at the University of Bristol in England said in a call with reporters. “We just don’t know at this point.”

A few people given other COVID-19 vaccines have also developed rare clots; for example, three people in the European Union and United Kingdom developed them after getting Johnson & Johnson’s jab. But those shots have not been not linked with clotting issues, Peter Arlett, head of data analytics and methodology at the EMA, said at the news conference.

Determining how often people actually do develop blood clots after their shots is difficult, since the committee is relying on vaccinated people to report their symptoms rather than routine monitoring done by experts, Straus said. So far, the reported rate differs among EU countries. In Germany, for instance, the reported rate is around 1 case of blood clots per 100,000 people while it is around 1 case per 600,000 people in the United Kingdom, Straus said. Normally, there are 1 to 2 cases per 100,000 people.

While the numbers are hard to parse, the reported rate of blood clots post-vaccination is still lower than that of other common medications that carry risks of the same medical issue. For women taking oral contraceptives, for instance, the rate of blood clots is 4 cases per 10,000, Arlett said.

Although most of the rare blood clots have occurred in women younger than 60 years old, the factors that could put people at risk of forming clots remain unclear, Straus said. That’s in part because some of the records do not provide all the necessary information about the people who developed clots, such as age or gender. More women than men have received the shot overall in the European Union and United Kingdom, which could also skew the results.

Even without clear information on risk factors, many countries have placed restrictions on the use of AstraZeneca’s vaccine. Some countries, including Denmark and Norway, have stopped using the shot. Others, like Canada and Germany, are using it only to vaccinate older adults. On April 6, the United Kingdom paused an ongoing trial of AstraZeneca’s vaccine in children 6 to 17 years old. U.K. officials now recommend that health experts offer other COVID-19 vaccines to people younger than 30 years old.

In the United States, AstraZeneca plans to apply soon for emergency use authorization from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes  What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?

What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?  This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces

This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces  Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now

Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now  Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight

Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight  A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?

A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?