In December 2020, health officials in the United Kingdom announced that a new coronavirus variant was rapidly spreading across the region. Weeks later, U.S. officials found the first case in the United States (SN: 12/22/20). And by early April, the variant had become the most common form of the coronavirus identified across the country, an event that the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had warned in January might happen (SN: 1/15/21)

The news came amid a surge in coronavirus cases in many states, including Michigan, where the new variant, dubbed B.1.1.7, makes up nearly 58 percent of genetically screened samples collected as of March 27. The variant is less prevalent in California, New York and other states, where homegrown versions of concerning coronavirus variants are currently causing the majority of cases instead.

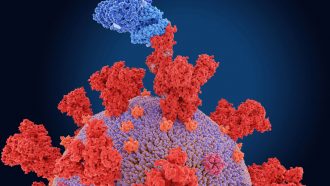

Following the emergence of the variant in the United Kingdom, scientists have worked to get a handle on how mutations in the virus’s genetic blueprint might change its behavior, amid concerns that the virus might have gained the ability to evade vaccines or cause more severe disease. Here’s what researchers have learned so far about B.1.1.7.

B.1.1.7 is 40 to 70 percent more transmissible than other variants.

Rapid spread of the coronavirus among people in a corner of London that was linked to the emergence of a variant was what first raised health officials’ concerns. In the months since, multiple studies support that initial finding that B.1.1.7 is more contagious than previous versions of the virus, on the order of around 40 to 70 percent.

The current hypothesis for why the variant is more transmissible is that a mutation in the spike protein — which helps the coronavirus break into cells — allows the virus to attach more tightly to the cellular protein that lets it enter a new cell. That leads to a higher amount of virus in the body and a more transmissible virus, says Eleni Nastouli, a clinical virologist at University College London.

Another possibility is that B.1.1.7 hangs out in the body for longer than other variants, giving people more time to transmit it. Or it could cause certain symptoms, such as a cough, more frequently, which might help the virus spread. A study conducted through the U.K. Office for National Statistics, for example, previously found that those infected with the variant were slightly more likely to have cough, sore throat, fatigue or muscle pain. But a more recent study counters those results. Among 36,920 people living in the United Kingdom who used an app to report COVID-19 symptoms, there were no differences in symptoms linked to B.1.1.7 compared with ones caused by other versions of the coronavirus, researchers report April 12 in the Lancet Public Health.

“We need a bit more work to find out what’s really going on,” says Mark Graham, a medical imaging expert at King’s College London who led the new work. But overall, there are no dramatic changes, he explains. “It’s not like suddenly you don’t get loss of smell with B.1.1.7 or anything like that. All the key symptoms are there.”

Overall, B.1.1.7 is probably more lethal, too.

One worrying trait that has emerged is that B.1.1.7 seems to be more lethal than other versions of the coronavirus. Infection with the variant raises the risk of death overall by around 60 percent, studies suggest.

Zeroing in on hospitalized patients, a group at high risk of death, however, reveals no link between infections with B.1.1.7 and risk of severe disease or death, Nastouli and her colleagues report April 12 in the Lancet Infectious Diseases. “That is obviously a positive message,” Nastouli says. Still, “it doesn’t mean that it is a less deadly virus.”

That’s because B.1.1.7 spreads more easily than other variants, meaning it can infect more people, some of whom will die. More are likely to end up in the hospital, compared with previous variants, “but the moment that you come to the hospital, you having the variant doesn’t make a difference in terms of your outcome of severity and death,” Nastouli says. The researchers didn’t see an increased risk of death even after adjusting for factors such as age, underlying conditions or ethnicity.

That finding still fits with the current evidence hinting that the virus is more deadly overall, says Nicholas Davies, an evolutionary biologist and epidemiologist at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine who was not involved in the work.

Still, studies done outside of the United Kingdom are needed to confirm the results, Davies and Nastouli say.

Vaccines — and prior infection — still appear to protect people from B.1.1.7.

Although some mutations seen in B.1.1.7 raised concerns that the variant could dodge parts of the immune response, evidence is building that vaccines and previous infections are still protective.

The April 12 Lancet Public Health study, for instance, did not find evidence that B.1.1.7 caused a surge in reinfections in the United Kingdom as the variant rose to dominance in December 2020, Graham says. “That might suggest that B.1.1.7 is not able to evade immunity that people have acquired from infections to previous strains.”

Recent data from Israel — a country that has vaccinated more than half its population — also suggest that B.1.1.7 is not infecting people who are fully vaccinated with Pfizer’s jab, instead primarily infecting those who are unvaccinated or partially immunized, researchers report in a preliminary study posted April 9 at medRxiv.org.

So, for now, “we don’t really have to worry about alternative vaccines” for B.1.1.7, Graham says. Current vaccines “do work against it.”

Researchers have their eyes on other variants.

While B.1.1.7 poses threats because of its rapid spread and increased risk of hospitalization, other variants are also worrisome. That’s in part because while vaccines still appear to work for B.1.1.7, the shots might be less effective against other variants of the virus.

Studies done in lab dishes hint that a variant called B.1.351, first identified in South Africa, can evade some antibodies from vaccinated people or those who had been infected with other variants (SN: 1/27/21). But the immune response is multifaceted, so researchers need data from the real world to pinpoint the effect on vaccines.

The study in Israel found that people fully vaccinated with Pfizer’s shot were more likely to be infected with B.1.351 compared with other variants. But there were few cases with B.1.351 overall, suggesting the actual odds of infection are still unknown. In a small trial in South Africa with 800 participants, however, where B.1.351 is prevalent, nine out of nine COVID-19 cases were in people who did not receive Pfizer’s shot, the pharmaceutical company announced April 1. That hints that the shot is likely still effective against B.1.351, which caused six of those cases.

Another variant dubbed P.1, found in Brazil, also appears to be more transmissible than earlier strains (SN: 4/14/21). People who have already recovered from COVID-19 have around 54 to 79 percent of protection against P.1 as they do against other variants circulating in the country. It is still unclear how protective currently authorized vaccines might work against P.1.

That’s particularly worrisome as COVID-19 cases are climbing in countries such as Brazil and India. A variant with two key mutations thought to increase transmission and allow the virus to evade the immune response, for instance, was recently identified in India and has since spread to other countries. Amid such surges, additional new variants could emerge, which may put the end of the pandemic further out of reach.

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes  What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?

What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?  This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces

This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces  Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now

Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now  Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight

Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight  A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?

A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?