As coronavirus cases in the United States and around the world rise, scientists are uncovering hints that immunity for those who have had COVID-19 can last at least six months, if not longer.

After people with COVID-19 have largely recovered, immune proteins called antibodies are still detectable six months later. What’s more, the proteins have sharpened their skills at fighting the coronavirus, researchers report in a preliminary study posted November 5 at bioRxiv.org. Leftover pieces of the virus remaining in the gut after symptoms have disappeared may help the immune system work to refine that response.

The finding also bodes well for how long a vaccination might provide protection. Immunity from a vaccine is expected to last as long or longer than natural immunity.

Antibodies, which are immune proteins that bind to microbes to fight off an infection, are part of the body’s cache of immune defenses. People typically make a wide variety of antibodies during an infection. These proteins can recognize different surfaces on viruses — like a Swiss Army knife able to work on various parts of the virus — and evolve over time to better recognize their target (SN: 4/28/20).

Six months after an infection with the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, called SARS-CoV-2, people appear to have built an arsenal of antibodies that are not only more potent than the ones developed early on, similar to what has been seen in other infections. Those antibodies can also recognize mutated versions of the virus, researchers found. In addition to antibody upgrades, long-lasting immune cells that make antibodies, called memory B cells, stick around in the blood, poised to launch a rapid response should people be exposed to the virus again.

“The main message is that the immune response persists,” says Julio Lorenzi, a viral immunologist at the Rockefeller University in New York City. “We see these B cells surviving over time and the antibodies six months after infection are even better than the beginning of the infection.”

In the study, Lorenzi and colleagues analyzed the antibodies that 87 people made against the coronavirus at one and six months after developing symptoms. Although antibody levels in the blood waned, the immune proteins were still detectable after six months. Importantly, levels of memory B cells were stable, an assessment of 21 of the 87 participants showed — a sign that those cells may remain in the body for a while.

Other studies have hinted that B cells can persist for more than six months in recovered COVID-19 patients. Preliminary results of one study uncovered that memory B cells — as well as other cells involved in immune memory known as T cells — decline slowly in the blood, researchers reported November 16 at bioRxiv.org. That slow decrease could mean that immunity might last for years, at least in some people (SN: 10/19/20).

What’s more, Lorenzi and his team found, B cells refined the antibodies they made over a five-month time span to generate proteins that are better at recognizing the coronavirus. In an analysis of cells from six people, the researchers discovered changes in the genetic instructions that B cells use to make antibodies, a sign that the B cells were making new variations.

Some of the newer antibodies were better at stopping viruses from infecting new cells, and some could even attach to viruses with mutations in the spike protein, which helps the coronavirus break into host cells. Such widely binding antibodies could make it harder for the virus to escape recognition by the immune system.

The findings are encouraging, experts say, although it’s still unclear whether people with signs of immunity such as antibodies are completely protected from reinfection — called sterilizing immunity — or whether they would just become less severely ill if reinfected.

“When the first studies started coming out about antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2, everyone was in an uproar about the response being potentially defective,” says Nina Luning Prak, an immunologist at the University of Pennsylvania. Earlier results had hinted that antibody-generating B cells were poorly trained to make the immune proteins, perhaps because structures called germinal centers that teach the cells what parts of a virus the antibodies should bind to didn’t properly form.

That may have left it up to other immune signals besides germinal centers to activate B cells, leading to the production of less effective antibodies that might latch onto parts of the virus weakly. “As a result, [some scientists thought that] perhaps [B cells] made antibodies that were not so great,” Luning Prak says.

But that may be part of a normal immune response, Luning Prak says. Or defective germinal centers might appear in the most severe COVID-19 cases where “it’s an all-hands-on-deck style immune response” with lots of inflammation. When people survive the infection, researchers are now beginning to find that “when you look [at COVID-19 patients] six months out, antibody responses look far more conventional,” she says.

B cells may learn how to make better SARS-CoV-2 antibodies over time, with the help of a store of viral proteins that stays hidden in the gut after the virus is cleared from the rest of the body. Since the pandemic’s early days, researchers have documented the presence of coronavirus genetic material in the stool of some infected people.

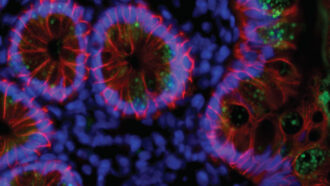

In the new study, seven of 14 recovered COVID-19 patients had evidence of coronaviruses in their intestinal tissue, the researchers found. Electron microscopy images of a sample from one patient revealed what look like intact virus particles adorned with a crown of spike proteins, a distinctive feature of coronaviruses.

Right now, it’s unclear whether the viral bits seen in the gut are in fact helping the immune system evolve to better recognize the coronavirus, much less whether those pieces come from infectious or dead viruses, Lorenzi says. “That’s a possibility,” but researchers need to study more people to figure that out.

Three Truths to Address Sexual Exploitation, Abuse & Harassment in the UN

Three Truths to Address Sexual Exploitation, Abuse & Harassment in the UN  COP27 Fiddling as World Warms

COP27 Fiddling as World Warms  UN chief highlights crucial role of G20 in resolving global crises

UN chief highlights crucial role of G20 in resolving global crises  Somalia: Human rights chief decries steep rise in civilian casualties

Somalia: Human rights chief decries steep rise in civilian casualties  Ukraine: UN convoy delivers vital aid to residents of Kherson

Ukraine: UN convoy delivers vital aid to residents of Kherson  COP27: Week two opens with focus on water, women and more negotiations on ‘loss and damage’

COP27: Week two opens with focus on water, women and more negotiations on ‘loss and damage’  A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes  What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?

What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?  This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces

This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces  Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now

Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now