Fifteen years of grading warming’s impact on the Arctic has made one thing abundantly clear: Climate change has drastically altered the Arctic in that short time period.

Breaking unfortunate records is “like whack-a-mole,” says Jackie Richter-Menge, a climate scientist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and an editor of the 2020 Arctic Report Card, released December 8 at the virtual meeting of the American Geophysical Union. From sea ice lows to temperature highs, records keep popping up all over the place. For instance, in June, a record-high 38° Celsius (100.4° Fahrenheit) temperature was recorded in the Arctic Circle (SN:6/23/20). And in 2018, winter ice on the Bering Sea shrank to a 5,500 year low (SN:9/3/20).

“But quite honestly, the biggest headline is the persistence and robustness of the warming,” Richter-Menge says. In 2007, only a year after the first Arctic Report Card, summer sea ice reached a record low, shrinking to an area 1.6 million square kilometers smaller than the previous year. Then, only five years later, the report card noted a new low, 18 percent below 2007. In 2020, sea ice didn’t set a record but not for lack of trying: It still was the second lowest on record in the last 42 years.

“The transformation of the Arctic to a warmer, less frozen and biologically changed region is well under way,” the report concludes. And it’s changing faster than expected when researchers launched the report card in 2006. The annual average air temperature in the Arctic is rising two to three times faster than the rest of the globe, Richter-Menge says. Over the last 20 years, it’s warmed at a rate of 0.77 degrees C per decade, compared with the global average of 0.29 degrees C per decade.

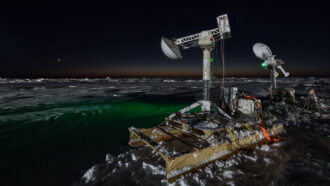

Improvements in research techniques over the last 15 years have helped researchers more thoroughly observe warming’s impact and how different aspects of Arctic climate change are linked to one another, she says. These improvements include the ability to measure ice mass via gravity measurements taken by the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) satellite. Other satellites have provided additional observations from above while on-the-ground measurements, such as by the Multidisciplinary drifting Observatory for the Study of Arctic Climate (MOSAiC), have provided up-close sea ice measurements (SN:4/8/20). The report has also begun to include on-the-ground observations of the Arctic’s Indigenous people, who experiences these changes directly (SN:12/11/19).

The changes have revealed few bright spots but one is the rebound of bowhead whales, which were hunted almost to extinction around the turn of the 20th century. While researchers are careful to note that the whales are still vulnerable, the four populations of the whales (Balaena mysticetus) now range from 218 in the Okhotsk Sea to around 16,800 in the Bering, Chukchi and Beaufort seas. Researchers suggest that the whales’ rebound is due, at least in part, to the warming that has occurred over the last 30 years. Earlier sea ice melting and warmer surface water means more krill and other food for these baleen feeders.

But don’t be fooled. The potential good news is overshadowed by the bad news. There’s been “this accumulation of knowledge and insights that we’ve gained over 15 years,” says Mark Serreze, a climate scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colo., who wasn’t involved in this year’s report. The 2020 research is “an exclamation point on the changes that have been unfolding,” he says. “The bowhead whales are doing OK, but that’s about it.”

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes  What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?

What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?  This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces

This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces  Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now

Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now  Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight

Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight  A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?

A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?