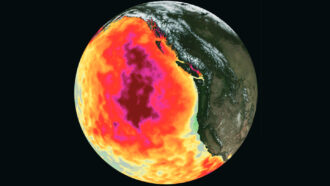

Yesterday’s scorching ocean extremes are today’s new normal. A new analysis of surface ocean temperatures over the past 150 years reveals that in 2019, 57 percent of the ocean’s surface experienced temperatures rarely seen a century ago, researchers report February 1 in PLOS Climate.

To provide context for the frequency and duration of modern extreme heat events, marine ecologists Kisei Tanaka, now at the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration in Honolulu, and Kyle Van Houtan, now at the Loggerhead Marinelife Center in Juno Beach, Fla., analyzed monthly sea-surface temperatures from 1870 through 2019, mapping where and when extreme heat events occurred decade to decade.

Looking at monthly extremes rather than annual averages revealed new benchmarks in how the ocean is changing. More and more patches of water hit extreme temperatures over time, the team found. Then, in 2014, the entire ocean hit the “point of no return,” Van Houtan says. Beginning that year, at least half of the ocean’s surface waters saw temperatures hotter than the most extreme events from 1870 to 1919.

Marine heat waves are defined as at least five days of unusually high temperatures for a patch of ocean. Heat waves wreak havoc on ocean ecosystems, leading to seabird starvation, coral bleaching, dying kelp forests, and migration of fish, whales and turtles in search of cooler waters (SN: 1/15/20; SN: 8/10/20).

In May 2020, NOAA announced that it was updating its “climate normals” — what the agency uses to put daily weather events in historical context — from the average 1981–2010 values to the higher 1991–2020 averages (SN: 5/26/21).

This study emphasizes that ocean heat extremes are also now the norm, Van Houtan says. “Much of the public discussion now on climate change is about future events, and whether or not they might happen,” he says. “Extreme heat became common in our ocean in 2014. It’s a documented historical fact, not a future possibility.”

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes  What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?

What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?  This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces

This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces  Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now

Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now  Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight

Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight  A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?

A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?