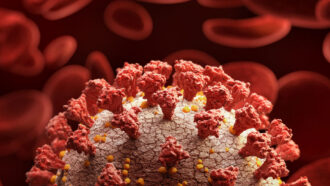

In a few weeks, dozens of young and healthy volunteers in the United Kingdom will be intentionally exposed to the coronavirus as part of the world’s first COVID-19 human challenge trial.

The project, which received ethics approval February 17 from the U.K. government, will study how much virus is required to kick-start an infection. Eventually, researchers could then address other questions, like how well different vaccines work.

In human challenge trials, volunteers are deliberately infected with a pathogen in a controlled environment. Researchers can then closely study the progression of disease or potential treatments with a level of detail largely unavailable in traditional trials, which require waiting for participants to pick up the disease on their own.

The possibility of COVID-19 challenge trials have stirred controversy; some question the ethics of putting volunteers at risk from a relatively new pathogen whose long-term consequences aren’t fully understood (SN: 5/27/20). For this trial, the promise of accelerated research outweighs the risks to participants, U.K regulators say.

“I think a case could be made that the risks are acceptable for young, healthy volunteers,” says Seema Shah, a bioethicist at Northwestern University Medical School in Chicago who is not involved in the trial. “People might still disagree,” she adds, “especially with the uncertainty about longer term morbidity.”

Within a month, researchers hope to enroll up to 90 healthy volunteers ages 18 to 30 who haven’t contracted the coronavirus. People under 30 are generally at a lower risk of hospitalization or death than older people, but serious illness can still occur (SN: 9/9/20).

In isolated hospital rooms, volunteers will be exposed to varying levels of an original coronavirus variant that’s been circulating since March 2020. Volunteers will then be monitored round-the-clock, allowing researchers to determine the minimum dose of coronavirus required to start infection, Andrew Catchpole, chief scientific officer at hVIVO, a pharmaceutical services clinical research organization in London that will help run the trial, said in a news statement. Figuring out how much exposure leads to infection is one of the longstanding open questions of the COVID-19 pandemic. Researchers can also track a volunteer’s immune response over the course of infection.

The answers to these basic research questions lay the groundwork for future studies. For instance, knowing the minimum infectious dose could enable future, yet-to-be-approved challenge trials that try to test vaccine candidates, or determine whether new variants of the virus can dodge naturally acquired immunity.

Such questions are important to answer, says Shah, but with coronavirus variants that are more contagious, and perhaps more deadly, now becoming dominant, it raises the question of how much impact this trial can have (SN: 1/15/21). They may behave differently than the strain used for this trial, weakening the broader applicability of its results.

For example, a future trial that does head-to-head comparisons of vaccine candidates could be valuable, but, Shah asks, “if you’re doing a challenge trial with a strain that is eventually no longer the dominant strain, what does that tell you about vaccine efficacy?”

Precisely how this newly approved human challenge will work remains unclear, as the details haven’t been made public. The researchers say they plan to publish the protocol and an explanation of the study design at some point in the future.

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes  What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?

What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?  This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces

This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces  Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now

Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now  Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight

Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight  A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?

A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?