CHERNOBYL Ukraine: A soft snow fell as a clutch of visitors equipped with a Geiger counter wandered through the ghostly Ukrainian town of Pripyat, frozen in time since the world’s worst nuclear accident in 1986.

More than three decades after the Chernobyl nuclear disaster forced thousands to evacuate, there is an influx of visitors to the area that has spurred officials to seek official status from UNESCO.

“The Chernobyl zone is already a world famous landmark,” guide Maksym Polivko told AFP during a tour on a recent frosty day.

“But today this area has no official status,” the 38-year-old said of the exclusion zone where flourishing wildlife is taking over deserted Soviet-era tower blocks, shops and official buildings.

That could be set to change under the government initiative to have the area included on the UNESCO heritage list alongside landmarks like India’s Taj Mahal or Stonehenge in England.

Officials hope recognition from the UN’s culture agency will boost the site as a tourist attraction and in turn bolster efforts to preserve aging buildings nearby.

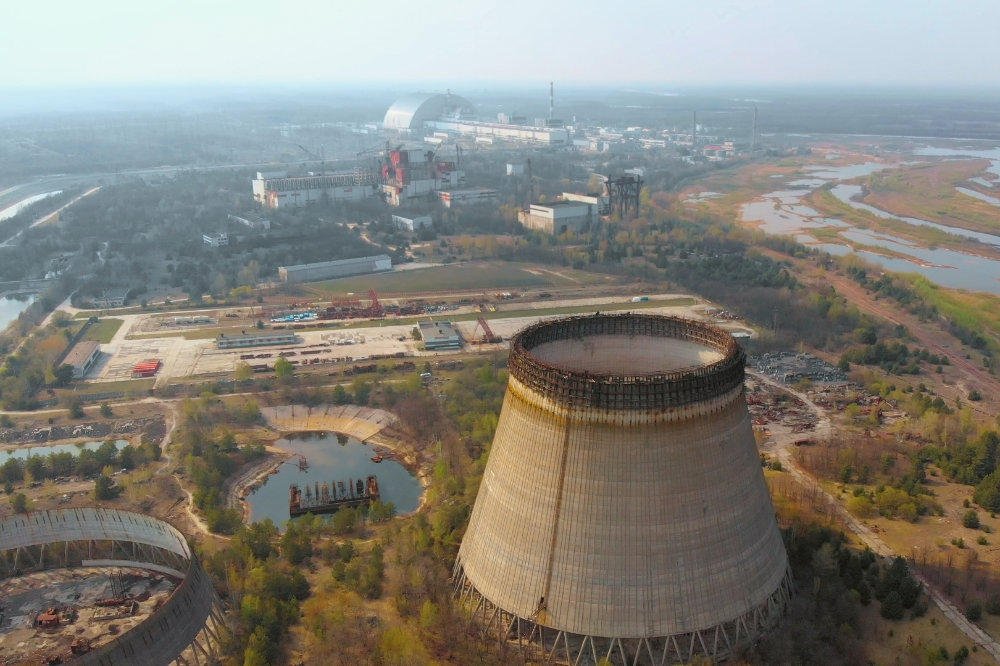

The explosion in the fourth reactor at the nuclear power plant in April 1986 left swathes of Ukraine and neighboring Belarus badly contaminated and led to the creation of the exclusion zone roughly the size of Luxembourg.

Ukrainian authorities say it may not be safe for humans to live in the exclusion zone for another 24,000 years. Meanwhile, it has become a haven for wildlife with elk and deer roaming nearby forests.

Dozens of villages and towns populated by hundreds of thousands of people were abandoned after the disaster, yet more than 100 elderly people live in the area despite the radiation threat.

In Pripyat, a ghost town kilometers away from the Chernobyl plant, rooms in eerie residential blocks are piled up with belongings of former residents.

Polivko said he hoped the upgraded status would encourage officials to act more “responsibly” to preserve the crumbling Soviet-era infrastructure surrounding the plant.

“All these objects here require some repair,” he said.

It was a sentiment echoed by Ukrainian Culture Minister Oleksandr Tkachenko, who described the recent influx of tourists from home and abroad as evidence of Chernobyl’s importance “not only to Ukrainians, but of all mankind.”

A record number of 124,000 tourists visited last year, including 100,000 foreigners following the release of the hugely popular Chernobyl television series in 2019.

Tkachenko said obtaining UNESCO status could promote the exclusion zone as “a place of memory” that would warn against a repeat nuclear disaster.

“The area may and should be open to visitors, but it should be more than just an adventure destination for explorers,” Tkachenko told AFP.

The government is set to propose specific objects in the zone as a heritage site before March but a final decision could come as late as 2023.

After the explosion in 1986, the three other reactors at Chernobyl continued to generate electricity until the station finally closed in 2000. Ukraine will mark the 20th anniversary of the closure on December 15.

Tkachenko said the effort to secure UNESCO status was a new priority after work on a giant protective dome over the fourth reactor was completed in 2016.

With the site now safe for one hundred years, he said he hoped world heritage status would boost visitor numbers to one million a year.

It’s a figure that would require an overhaul of the local infrastructure and overwhelm a lone souvenir kiosk on the site selling trinkets such as mugs and clothing adorned with nuclear fallout signs.

“Before, everyone was busy with the cover,” Tkachenko said of the timing of the heritage initiative.

“The time has come to do this.”

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes  What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?

What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?  This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces

This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces  Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now

Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now  Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight

Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight  A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?

A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?