Before Russia invaded Ukraine, many military analysts feared that the capital of Kyiv would fall within days of an attack, undermining any further resistance. Instead, the war is well into its second month. Ukrainian fighters have reversed some Russian gains, forcing a retreat from Kyiv and an apparent narrowing of Russia’s sights to the country’s eastern provinces, closest to Russia’s border.

What these analysts and Russian President Vladimir Putin himself missed, social scientists say, is research showing that people who live within the borders of Ukraine have identified more and more as Ukrainian — and less as Russian — since Ukraine’s independence from the former Soviet Union in 1991.

That trend intensified after Russia seized the Crimean Peninsula in 2014 and started backing separatists in the Donbas region, political and ethnic studies scholar Volodymyr Kulyk said in a virtual talk organized by Harvard University in February. “Russians came to mean people in Russia,” said Kulyk, of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine in Kyiv.

These Ukrainian loyalists are now fighting tooth and nail for their country’s continued, sovereign existence.

“Putin underestimated Ukrainians’ attachment to their country and overestimated [their] connection to Russia,” says political scientist Lowell Barrington of Marquette University in Milwaukee. “One of his biggest mistakes was not reading social science research on Ukraine.”

Historic divide

The common refrain is that Ukraine is a country divided along both linguistic and regional lines, political scientists Olga Onuch of the University of Manchester in England and Henry Hale wrote in 2018 in Post-Soviet Affairs.

While the official language of Ukraine is Ukrainian, most people speak both Ukrainian and Russian. People living in western cities, most notably Lviv, primarily speak Ukrainian and those in eastern cities closer to the Russian border primarily speak Russian.

The origins of those divisions are complicated, but can be traced back, in part, to between the late 18th century and early 20th century when western Ukraine was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and eastern Ukraine was part of the Russian Empire. Then, after the collapse of the Russian Empire in 1917, Ukraine was briefly an independent state known as the Ukrainian People’s Republic before being incorporated into the Soviet Union in the early 1920s.

This map, published in 1918 in the New York Times, shows the boundaries of the short-lived Ukrainian People’s Republic. Other lands to the west that were part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire were later added before the entire republic was incorporated into the Soviet Union in the early 1920s.The New York Times/Wikimedia Commons

Putin seems to believe that national identities stay relatively fixed across time, says Hale, of George Washington University in Washington, D.C. Social scientists refer to that idea as primordialism, the belief that individuals have a single nationalistic or ethnic identity that they pass on to subsequent generations. In other words, once a Russian, always a Russian.

That rigid mentality shows up in official documents and censuses conducted in the Soviet Union starting in 1932. That’s when government officials began recording every citizen’s natsionalnist, essentially a conflation of nationality with ethnicity. People in the Soviet Union fell into one of over 180 possible ethnic categories, such as Russian, Chechen, Tatar, Jewish or Ukrainian, political scientists Oksana Mikheieva and Oxana Shevel wrote in 2021 in a chapter of the book From ‘the Ukraine’ to Ukraine.

“Nationality was transformed into a characteristic of a person that was inherited from his parents, rather than chosen consciously,” says Mikheieva, a political scientist at the European University Viadrina in Frankfurt and the Ukrainian Catholic University in Lviv.

While the Kremlin’s goal was to unite people of different nationalities under a single Soviet label, those with a Russian ethnicity remained at the top of the social ladder, write Mikheieva and Shevel, of Tufts University in Medford, Mass . Paradoxically, one’s nationality both provided a sense of belonging and deepened ethnic divides.

Putin, who served in the Soviet-era KGB, may have either directly or indirectly been counting on people to still view their nationality in this way. “He’s stuck in his formative years from the Soviet period,” says Elise Giuliano, a political scientist at Columbia University.

Shifting identity

Today, primordialism has largely fallen out of favor among social scientists, Hale says. Most researchers now see ethnic and nationalistic identities as fluid, evolving and dependent on the political and social environment. Individuals may also consider themselves to have multiple ethnicities.

Some of that shift in thinking comes from the study of Ukraine itself. The country’s relatively recent independence in 1991 means that social scientists can track the Ukrainian people’s evolving sense of identity in real time. And Ukraine also made the unusual move of granting citizenship to nearly everyone living within its territorial borders at the time of independence. When Ukrainian passports became available in 1992, officials likewise stopped the Soviet practice of stamping them with the owner’s natsionalnist. During the 2000s, that category also disappeared from birth certificates.

These practices contrasted with countries such as Latvia and Estonia, which refused automatic citizenship to ethnic Russians in their countries, says Barrington, the Marquette political scientist. Consequently, Ukraine paved the way for the emergence of a civic, or chosen, identity.

In studying post-Soviet Ukraine, researchers wanted to know: Would people living in Ukraine, even those with non-Ukrainian natsionalnists, shed their Soviet identity and become Ukrainian?

Official censuses conducted before and after independence hinted that the percentage of people living in Ukraine and identifying as Ukrainian did increase after 1991. In 1989, about 22 percent of people identified as Russian, but by 2001, only about 17 percent did. Migration out of Ukraine cannot fully account for that change, researchers say.

Since 2001, no national censuses have been held in Ukraine. So scientists have instead had to rely on smaller but often more detailed surveys, many generated in collaboration with the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology. Initially, researchers continued to use Soviet terminology on those surveys. Censuses and surveys shoehorn people into categories, Hale says, but understanding how people’s interpretation of those categories change over time, particularly when the social context changes, is useful (SN: 3/8/20). Researchers thus needed to look into what people meant when they chose a certain answer.

That work started with the “native language” question on surveys, which even in Soviet times was hard for researchers to interpret. Asking people what they considered to be their native language was meant to capture their language of everyday use. But people often selected the language that aligned with their ethnicity.

For instance, about 12 percent of Ukrainians selected Russian as their native language on the 1989 census, Kulyk, the political and ethnic studies scholar at the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, said in his talk. But other surveys conducted around that time that did distinguish between native language and language of everyday use revealed that over 50 percent of Ukrainians spoke Russian in everyday life.

That confusion surrounding the native language question carried over to post-Soviet Ukraine. Surveys conducted in the 1990s and 2000s showed that many people selecting Ukrainian as their native language did not necessarily speak the language, Kulyk reported in 2011 in Nations and Nationalism.

In a more recent analysis of three nationwide surveys in Ukraine — conducted in 2012, 2014 and 2017, and each involving roughly 1,700 to 2,000 respondents — Kulyk investigated responses to the question: “What language do you consider your native language?” In 2012, some 60 percent of respondents said Ukrainian and 24 percent said Russian. By 2017, over 68 percent of respondents selected Ukrainian and just under 13 percent selected Russian, he reported in 2018 in Post-Soviet Affairs.

Those numbers say little about actual language use, Hale says. Instead, the native language question is a way to gauge people’s shifting views of national identity. The growing number of Ukrainian “speakers” and the decreasing number of Russian “speakers” suggests that people are selecting the answer that’s in line with their Ukrainian civic identity, he says. “Knowing Russian isn’t any kind of predictor for supporting the Russian state. Instead, what is [becoming] more important is the civic identification with the Ukrainian state.”

Choosing Ukraine

Researchers who study identity have also begun investigating Ukrainians’ responses to the question, “What is your natsionalnist?” which still occasionally appears on official paperwork, Mikheieva says.

Ukrainians filling out those forms can interpret the term as asking about their ethnic background in the Soviet sense, their chosen identity or some combination of both. What social scientists need to understand is how Ukrainians no longer under Soviet rule perceive themselves.

To that end, the three nationwide surveys Kulyk evaluated in his 2018 study all asked people multiple questions about nationality. In one, for instance, participants were told: “… some people consider themselves belonging to several nationalities at the same time. Please look at this card and tell which statement reflects more than the others your opinion about yourself.” People could then select a single nationality or some combination of Russian and Ukrainian nationalities. That work revealed that the percentage of people selecting only Ukrainian went up from 67.8 percent in 2012 to 81.5 percent in 2017.

What’s more, the greatest rise occurred among people living in the historically Russian strongholds of eastern and southern Ukraine. In 2012, some 40 percent of Ukrainians from that region selected “only Ukrainian” compared with almost 65 percent in 2017. Meanwhile, the percentage of eastern and southern Ukrainians identifying as “only Russian” decreased from roughly 17 percent in 2012 to less than 5 percent in 2017.

The actual percentage of Ukrainians allying with Russia might be slightly higher, however, as Kulyk and other researchers have been unable to collect more recent data from the Russian-controlled Crimean Peninsula and the disputed Donbas region.

More recent research also suggests that the Ukrainian people are gradually shedding their Soviet understanding of identity. For instance, in a 2018 survey of over 2,000 people, some 70 percent of respondents said that their Ukrainian citizenship constituted at least part of their identity, Barrington reported in 2021 in Post-Soviet Affairs. That’s due, in part, to Ukrainian leaders’ concerted efforts to shift away from ethnic nationalism and toward civic nationalism, Barrington wrote. Deprioritizing ethnicity weakens the linguistic and regional divides; civic nationalism, meanwhile, bonds people through “feelings of solidarity, sympathy and obligation.”

Russian President Vladimir Putin missed social science research showing Ukrainians’ strong and growing attachment to their country, scientists say. On March 14, three weeks into the war, volunteers in Lviv sew new Ukrainian flags.AP Photo/Bernat Armangue

Broadly speaking, researchers say, these surveys all show that identification with the Ukrainian state began immediately after the country achieved independence, and accelerated following Russian aggression in the region in 2014.

The current war, by extension, is almost certainly cementing many Ukrainians’ loyalty to their country, everyone interviewed for this story said. “In some paradoxical twist,” says Shevel. “Putin is basically unifying the Ukrainian nation.”

Identity grows stronger, and internal divisions weaker, when nations are under attack, says Giuliano, the political scientist at Columbia University. During an invasion, “you are going to rally around the flag. You’re going to support the country in which you live.”

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes

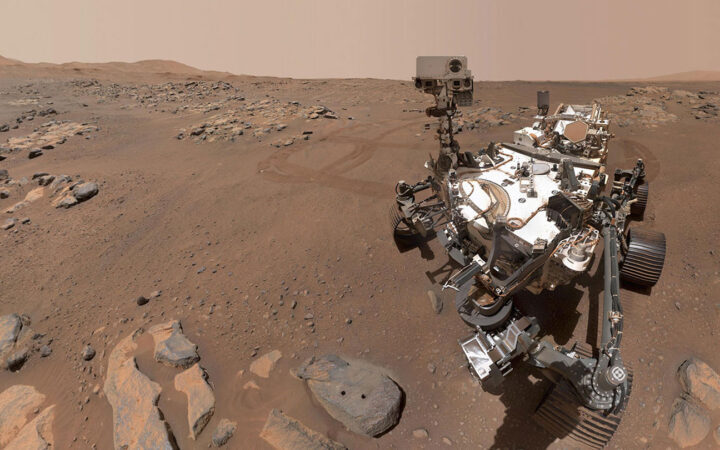

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes  What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?

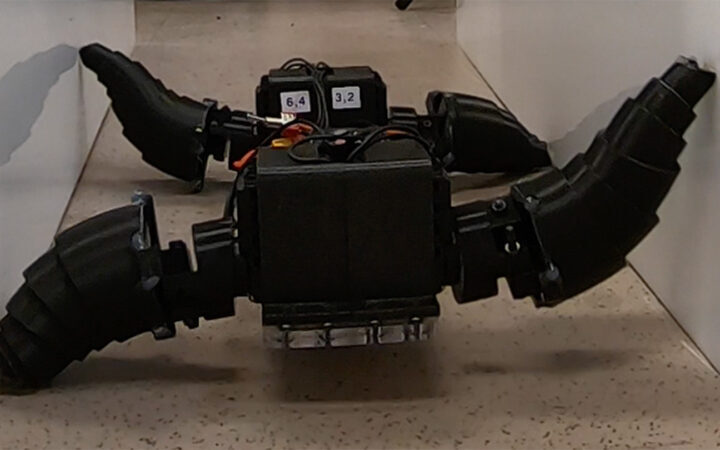

What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?  This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces

This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces  Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now

Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now  Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight

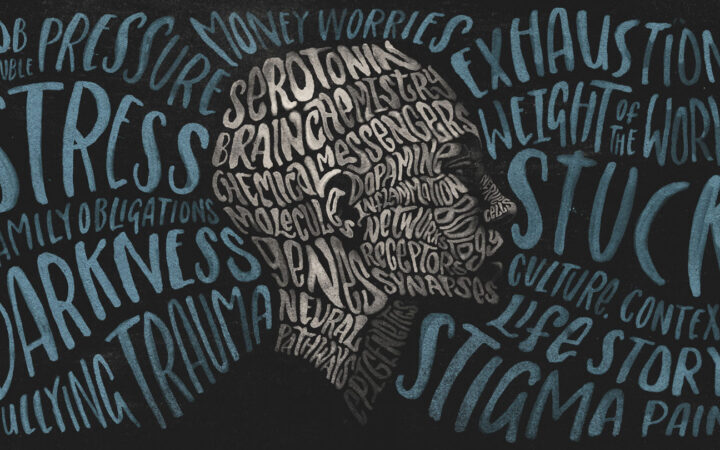

Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight  A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?

A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?