It may soon be too late to end the global monkeypox epidemic.

“We are losing the window to be able to contain this outbreak,” Boghuma Titanji, an infectious diseases doctor and virologist at Emory University in Atlanta said July 21 during a seminar sponsored by the Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs.

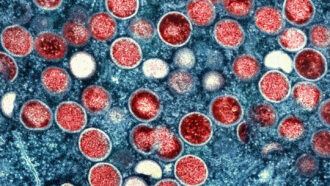

A global outbreak of monkeypox has infected more than 15,700 people since the beginning of May, according to Global.health (SN: 5/26/22). More than 2,800 cases have been reported in the United States as of July 22, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report. Titanji’s remarks came as the World Health Organization was again weighing whether the outbreak is a public health emergency of international concern, the organization’s highest state of alert.

Monkeypox has caused outbreaks for decades in some parts of Africa, Anne Rimoin, an epidemiologist at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, said at the Harvard seminar. But the virus “has been neglected by the global health community.” Monkeypox “has been giving us warning signals” for years in Congo, Nigeria and other parts of West Africa, but has only gotten attention once it recently started causing cases outside of the continent, Rimoin said.

There has been no concerted global effort to contain the virus, which is related to smallpox, Titanji said. Each country has been left to set its own policies.

That has led to disparities. Well-resourced countries have had at least some access to testing, vaccines and medications, which may help limit the spread of the virus or the severity of the disease. Resource-poor nations often lack that access, leaving them with limited ability to track or control the virus. Continued spread of monkeypox in resource-poor countries could leave places that do manage to contain an initial outbreak vulnerable to reintroductions, Jay K. Varma, director of the Cornell Center for Pandemic Prevention and Response in New York City, said in the seminar.

Even for the wealthiest countries, containing the outbreak is a challenge. Questions abound about how the virus is transmitted, and whether vaccines and treatments — when people can get them — can halt its spread. Even diagnosing the disease can be tricky, with testing often hard to come by and missed diagnoses potentially leading to more cases.

The vast majority of monkeypox cases in the global outbreak have been among men who have sex with men. Of 528 people infected with monkeypox in 16 countries, 98 percent identified as gay or bisexual men, researchers report July 21 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In some countries with outbreaks, “gay men are criminalized,” Kai Kupferschmidt, a correspondent for Science magazine, said during the seminar. In those countries, “people cannot access good information to help them keep from getting infected and cannot access health care if they do get infected. In these countries, it becomes really difficult to even see the problem,” he said.

Doctors might also miss cases of monkeypox because of the unusual presentation of the illness in this outbreak, compared with earlier outbreaks. For instance, in the NEJM study, only a quarter of patients had monkeypox lesions on their faces and only 10 percent had the sores on their palms or soles of their feet. Those body parts have been among some of the most affected in other outbreaks.

Instead, 73 percent of people in the study had lesions in the anal and genital regions and 55 percent on the trunk, arms or legs. Some people also had lesions in their mouths and throats. Most of the people in the study had fewer than 10 lesions, with 54 people having only a single lesion on their genitals, making confusion with herpes or syphilis possible, even easy.

Seventy people in the study were admitted to the hospital. Of those, 21 were hospitalized because of pain, mostly severe rectal pain. Others had eye lesions, kidney damage, inflammation of the heart or throat swelling that prevented them from taking in liquids.

Those complications fit with what health officials across the United States have been seeing. “While mortality appears very low, which is great, morbidity has been much higher than any of us expected,” Mary Foote, the medical director of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, said July 14 in a news briefing sponsored by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

“A lot of people with this infection are really suffering, and some may be at risk of permanent damage and scarring. We see many people with symptoms so severe that they are unable to go to the bathroom, urinate or eat without excruciating pain,” Foote said.

A small number of women and children have also gotten monkeypox in the outbreak. Two children in the United States have been diagnosed with monkeypox, CDC director Rochelle Walensky said July 22 in an interview with the Washington Post. Both children were social contacts of men that have sex with men, she said.

A child in the Netherlands who had no contact with anyone known to be infected with the virus also got monkeypox, researchers report July 21 in Eurosurveillance. His case raises the possibility that monkeypox may be spreading undetected more broadly in communities than realized.

“I don’t think it’s surprising that we are occasionally going to see cases in individuals who are not gay, bisexual or other men who have sex with men. The social networks we have as humans mean we have contact with a lot of different people,” Jennifer McQuiston, deputy director of the CDC’s Division of High Consequence Pathogens and Pathology said July 22 during a White House news briefing.

Exactly how the child in the Netherlands became infected is a matter of speculation. Monkeypox typically spreads among people through close contact with infected people or with clothing, bedding or towels used by people with the disease. Examination of viral DNA showed that the boy isn’t connected to any of the known cases in the Netherlands. He traveled to Turkey in June and may have gotten infected there or while traveling.

The boy has very low levels of IgA antibodies, which patrol mucous membranes and help prevent infections there. Low levels of the antibodies could make him vulnerable to respiratory infections. People can get infected with monkeypox through droplets given off by infected people during close face-to-face interactions, such as close conversation, kissing or during medical exams. But patterns of infection clearly indicate that monkeypox isn’t airborne the way COVID-19 or other respiratory viruses are, Kupferschmidt said.

Details of how monkeypox spreads are still unknown. For instance, researchers don’t know whether the virus can be transmitted through semen as a sexually transmitted disease. Researchers have found evidence of viral DNA in semen, saliva, urine and feces, but that may just be inactive remnants of the virus. So far, no researchers have reported finding infectious virus in genital body fluids that might be exchanged during sex. Also unknown is whether getting infected through mucous membranes during sexual contact would shield against catching the virus later, Rimoin said.

Scientists are questioning whether the monkeypox virus has changed or whether it has simply found a niche social-sexual network among gay and bisexual men that may enable the virus to spread more efficiently, Titanji said. It may be that there are different transmission patterns in historically affected countries and newly affected countries that require different strategies to stop the spread, she said.

Researchers also need to do good studies to figure out how well vaccines and therapeutics work and under what circumstances, Rimoin said.

One thing is clear, she said. “We’re giving this virus room to run like it never has before.” People have passed the buck, leaving others to work out the problem of monkeypox, she said. But now, “it’s everybody’s problem to solve.”

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes  What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?

What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?  This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces

This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces  Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now

Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now  Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight

Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight  A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?

A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?