LONDON: A British expert on terrorism law has claimed that deradicalization programs for convicted terrorists don’t work, calling them “deceptive” and likening convicted extremists to sex offenders who lie about being reformed to obtain release from prison.

The intervention comes against the backdrop of the UK attempting to introduce greater powers for authorities to monitor terrorists and extremists after they are released from prison.

Jonathan Hall, QC, told The Times that the public should be under “no illusion” that schemes to rehabilitate dangerous jihadists would be effective, saying there was no evidence to suggest they had much effect.

Hall, an independent reviewer of UK terror legislation, added that those released from prison should be placed under constant supervision and backed the government’s plans to ensure those released are subjected to regular lie-detection tests, or polygraphs, amid a raft of other measures.

“Terrorists are deceptive like sex offenders,” he told The Times. “It’s well documented — you get people who will say things just because they know that’s what people want to hear. And this is a really tricky issue.

“There is no magic bullet, there is no special pill you can take that deradicalizes people, whether they’re coming back from overseas from Syria, or whether they’re being released from prison,” he continued. “It’s a pretty difficult, complex and fraught process. You can’t tell the public that you can place someone with a theological mentor, and they’ll come out the other side. It’s far more difficult than that.”

But Hall dismissed the idea that all convicted extremists were beyond hope of redemption.

“I can see why people try, because if you didn’t try, it would be throwing away all hope, and these offenders are also subjected to some pretty major restrictions, so it’s worth giving them an opportunity to change,” he added. “And there will be some who will change, but you should be under no illusions: It is not some automatic process. And in many cases, it simply won’t work. It doesn’t mean it’s not worth trying.”

The UK has struggled in recent years with the issue of what to do with jihadists, from returning members of the militant group Daesh, such as Shamima Begum, to domestic terrorists.

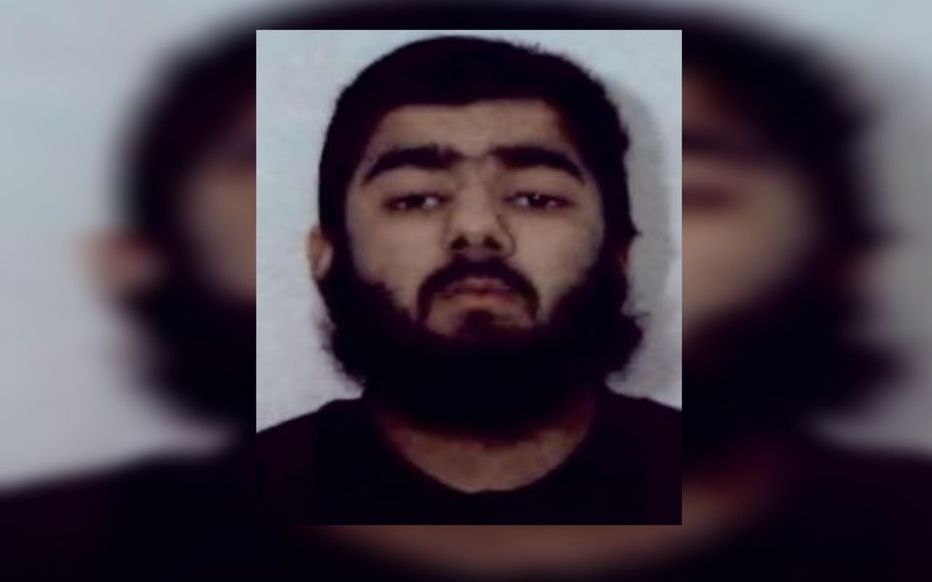

In 2019, Usman Khan stabbed two people to death on London Bridge, the site of a previous terrorist attack in 2017, before being shot by police. He was out of prison on license, and had been on the UK’s Desistance and Disengagement Programme (DDP), which included theological support and regular access to a psychologist.

Alongside the DDP, which is considered the most thorough program, the UK has two further deradicalization programs: Prevent, which seeks to stop people from becoming radicalized, and Channel, for those in the early stages of becoming extremists.

In February, Sudesh Amman stabbed two people in Streatham, south London, before being shot, having also been released on license following conviction for terror offenses, but was still deemed dangerous enough to warrant constant police monitoring.

After the Streatham attack, the UK government introduced the Terrorist Offenders Act the same month, to make it more difficult for convicted terrorists to be released.

UK government wins bid for Supreme Court to hear ‘Daesh bride’ Shamima Begum’s caseUK sees rise in Islamist extremist cases referred to counter radicalization program

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes  What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?

What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?  This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces

This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces  Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now

Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now  Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight

Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight  A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?

A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?