Imagine if, at the height of the 1918 flu pandemic, researchers studying how society was changing had captured the moment in a time capsule. What information might social scientists today have gleaned from such an effort? How might that repository inform the global response to the current pandemic? Theoretically such an artifact could be buried somewhere, but for now, researchers are out of luck.

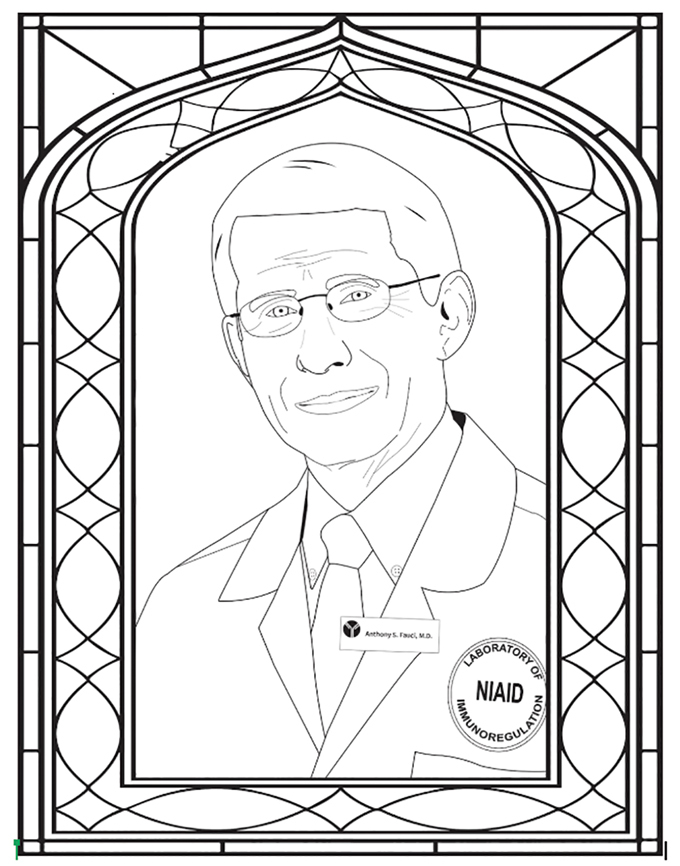

When the next pandemic invariably strikes, though, social scientists might find themselves better situated. The nonprofit Social Science Research Council, based in Brooklyn, N.Y., has assembled a collection of images that aims to freeze in time the myriad ways the COVID-19 crisis is transforming societies worldwide. And unlike time capsules of yesteryear, this version will live entirely online. The capsule currently includes an eclectic mix of photographs, charts and even a drawing appearing to depict infectious diseases expert Anthony Fauci as a saint.

Alondra Nelson, president of the council, says she and colleagues knew by spring that the pandemic was going to trigger massive societal change. Council staff came up with numerous initiatives to help scientists discuss and study those changes, including grants for COVID-19 research. With support from outside sponsors, council staffers also set up an essay forum in which scientists evaluated the pandemic from varying vantage points — from its effect on democracy to what society might look like in the aftertimes. The group also began a crowdsourced “syllabus” covering scholarly and creative writings addressing all things pandemic.

But Nelson also wanted to capture the flood of images emerging from such a massive global upheaval. That led to the idea of a visual time capsule. Starting in the spring, the council began asking prominent researchers to select any image that spoke to their understanding of the crisis and then explain the choice in an interview.

Some researchers honed in on how the pandemic illuminated the United States’ racial and socioeconomic disparities, while others went more obscure or even darkly humorous, including, for example, a graphic asking viewers if they want to pay by Visa, Mastercard or toilet paper. So far, the time capsule consists of 21 images and corresponding interviews.

What’s most striking when viewing the images in aggregate is that, in the midst of a pandemic that has taken more than 1.3 million lives as of mid-November, few images speak directly to death or dying. More common are depictions of everyday life, such as a screenshot of a virtual classroom. There are also individuals, mostly people of color, still going about their jobs in person: A Black worker cleans a chair in a U.S. Senate chamber. A Black bike messenger passes a boarded-up Louis Vuitton store to make a delivery.

This catalog is both academic and personal. Economic sociologist Brooke Harrington of Dartmouth College selected an image of a Danish mother and son waiting to enter a school building in April. Harrington says the photo is a reminder that had she stayed in Denmark, where she worked for nearly a decade, that could have been her standing in line with her own son. Instead, her boy is attending school from home, and Harrington, like so many working parents, especially mothers, is simultaneously juggling work and family. “If you’re asking me in my capacity as an individual trying to stay alive and do my job in 2020, this is what is at the forefront of my mind,” she told Science News.

The problem of shuttered day care and schools in the United States and elsewhere is ongoing. But other images in the collection remind present-day viewers of moments that may have already been forgotten amid a frenetic news cycle. Consider the image of the Diamond Princess cruise ship berthed in Yokohama, Japan. After hundreds of passengers fell ill with the coronavirus in February, nobody on the ship was allowed to disembark for weeks. Remember when the passengers’ plight was the news du jour? I didn’t.

Which perhaps illustrates the point of preserving these moments in perpetuity.

Three Truths to Address Sexual Exploitation, Abuse & Harassment in the UN

Three Truths to Address Sexual Exploitation, Abuse & Harassment in the UN  COP27 Fiddling as World Warms

COP27 Fiddling as World Warms  UN chief highlights crucial role of G20 in resolving global crises

UN chief highlights crucial role of G20 in resolving global crises  Somalia: Human rights chief decries steep rise in civilian casualties

Somalia: Human rights chief decries steep rise in civilian casualties  Ukraine: UN convoy delivers vital aid to residents of Kherson

Ukraine: UN convoy delivers vital aid to residents of Kherson  COP27: Week two opens with focus on water, women and more negotiations on ‘loss and damage’

COP27: Week two opens with focus on water, women and more negotiations on ‘loss and damage’  A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes  What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?

What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?  This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces

This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces  Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now

Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now