For the first time in almost half a century, scientists are going to get their hands on new moon rocks.

The Chinese space agency’s Chang’e-5 spacecraft, which landed on the moon around 10:15 a.m. EST December 1, will scoop up lunar soil from a never-before-visited region and bring it back to Earth a few weeks later. Those samples could provide details about an era of lunar history not touched upon by previous moon missions.

“We’ve been talking since the Apollo era about going back and collecting more samples from a different region,” says planetary scientist Jessica Barnes of the University of Arizona in Tucson, who works with lunar samples from the American and Soviet Union missions of the 1960s and 1970s. “It’s finally happening.”

Chang’e-5, the latest in a series of missions named for the Chinese moon goddess (SN: 11/11/18), took off from the China National Space Administration’s launch site in the South China Sea on November 23 and landed in volcanic flatlands on the northwest region of the moon’s nearside.

The lander, equipped with a scoop and a drill, will collect about two kilograms of soil and small rocks, possibly from as deep as two meters below the moon’s surface, says planetary scientist Long Xiao of China University of Geosciences in Wuhan.

The spacecraft has to work fast. With no internal heating mechanism, it has no defenses against the extremely cold lunar night, which can reach –170° Celsius. The entire mission has to fit within one lunar day, about 14 Earth days.

After the lander collects the sample, a small rocket will bring the lander and the sample back to the orbiter perhaps as early as December 3, although the Chinese space agency has not released the official schedule.

Once in orbit, the moon material will be packaged into a return capsule and sent back to Earth. The capsule is expected to land in the Inner Mongolia region by December 17.

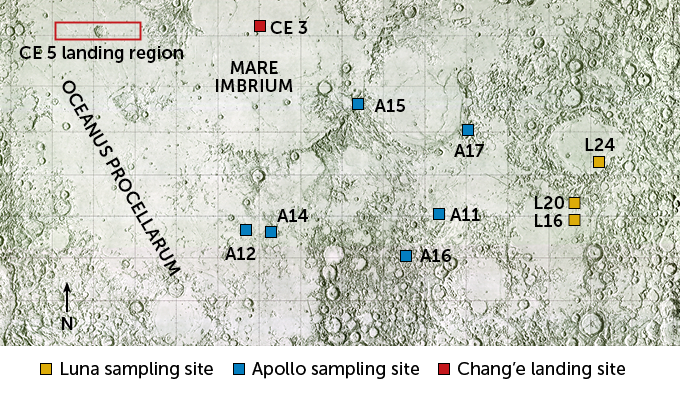

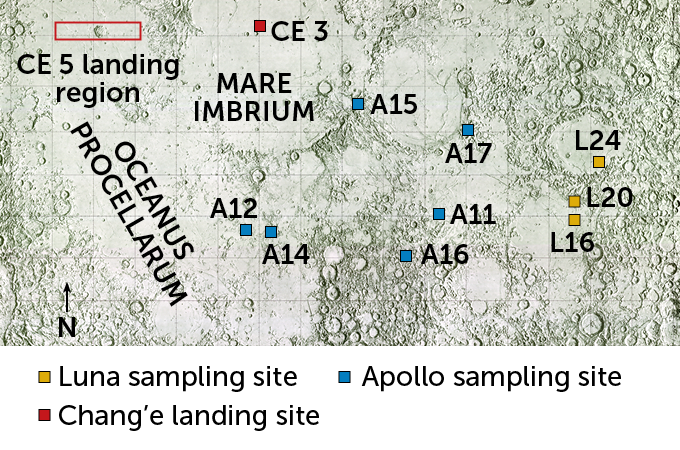

The last time new lunar samples were sent back to Earth was 1976, with the end of the Soviet Union’s Luna program. Between those missions and NASA’s Apollo missions, scientists on Earth have about 380 kilograms of moon material to study (SN: 7/15/19). “Perhaps for a long time people thought, been there, done that, when it comes to the moon,” Barnes says.

Two kilograms of new stuff might not sound like much next to what’s already in hand. But Chang’e-5 is returning samples from an entirely unexplored region. The landing site is in the Mons Rümker region in the northwest region of the nearside of the moon. Like the Apollo and Luna landing sites, Rümker is flat. “The engineering consideration is first, to be safe,” Xiao says.

All the Apollo and Luna missions visited ancient volcanic plains, where the rocks are between 3 billion and 4 billion years old. Rümker’s volcanic rocks are much younger, around 1.3 billion to 1.4 billion years old. In the ‘60s, scientists didn’t think the moon was still volcanically active that late. More recent studies from lunar orbit and from telescopes have suggested a more complicated volcanic past.

“With these new samples, we potentially add another pinpoint in our geologic history of the moon,” says Barnes. “We’ll get an idea of, what was the volcanic history like on the moon a billion years ago? That’s something we don’t have access to in the returned samples we already have.”

The Rümker region is also rich in potassium, rare-Earth elements and phosphorous, often called KREEP elements. Those elements were some of the last to crystalize out of the magma ocean that covered the young moon and can help reveal details of how that process happened. It’s an “exotic flavor” of material, says Barnes. “It’s a really different area, geochemically, to the rest of the moon.”

One of the biggest challenges for the mission will be drilling that material. The drill can’t change direction once it’s deployed, so it has to attempt to drill through anything directly below it. If the drill hits a large rock, it could fail. So the Chang’e-5 team is hoping for fine, loose soil, Long says.

Once the sample is back on Earth, it will be stored and cataloged at a curation center in Beijing. Then it will be distributed for scientists to do research.

“You can’t breathe easy on these types of missions until the samples are back and are safe in the curation place where they’re going to be held,” Barnes says.

The Chinese space agency plans to share samples with international scientists. A 2011 congressional rule makes it difficult for U.S. scientists to collaborate directly with China, so it’s unclear who will get to work with the rocks. But the discoveries that the new samples will enable go beyond international borders.

“It doesn’t matter who’s doing it,” says Barnes. “The whole world should be behind this mission and this endeavor. It’s a piece of history.”

Three Truths to Address Sexual Exploitation, Abuse & Harassment in the UN

Three Truths to Address Sexual Exploitation, Abuse & Harassment in the UN  COP27 Fiddling as World Warms

COP27 Fiddling as World Warms  UN chief highlights crucial role of G20 in resolving global crises

UN chief highlights crucial role of G20 in resolving global crises  Somalia: Human rights chief decries steep rise in civilian casualties

Somalia: Human rights chief decries steep rise in civilian casualties  Ukraine: UN convoy delivers vital aid to residents of Kherson

Ukraine: UN convoy delivers vital aid to residents of Kherson  COP27: Week two opens with focus on water, women and more negotiations on ‘loss and damage’

COP27: Week two opens with focus on water, women and more negotiations on ‘loss and damage’  A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes  What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?

What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?  This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces

This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces  Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now

Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now