A race to develop a COVID-19 vaccine began almost the minute the coronavirus’s genetic makeup was revealed in January.

Already, two companies have announced that their vaccines appear safe and about 95 percent effective (SN: 11/18/20, SN: 11/16/20). Government regulators in the United Kingdom granted permission December 2 for emergency use of a vaccine made by the pharmaceutical company Pfizer and its German biotech partner BioNTech. The first doses could be delivered within days of the announcement. Emergency use authorization and even full approval of the vaccines is probably not far off in the United States and other countries.

But another race is just beginning. Ultimately, the vaccines won’t truly be successful until enough people have gotten them to stop the spread of the virus and prevent severe disease and death. And that will pose a logistical challenge unlike any other.

In normal times, potential vaccines have only a 10 percent chance of making it from Phase II clinical trials — which test safety, dosing and sometimes give hints about effectiveness — to approval within 10 years, researchers reported November 24 in the Annals of Internal Medicine. On average, it takes successful vaccines over four years to go from Phase II trials to full regulatory approval.

Even if the COVID-19 vaccines made by Pfizer or by the biotechnology company Moderna are distributed in late December under emergency use provisions — less than a year after clinical trials began — they may not gain full approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for months, or even years. Even so, such lickety-split action to get out a vaccine against a previously unknown illness is unparalleled.

But though the race to make a COVID-19 vaccine is moving at a world-record pace, it is far from over, says Robin Townley in Washington, D.C., who heads special-projects logistics for A.P. Moller-Maersk, a company that handles supply chain logistics and transportation services for companies around the world.

“The vaccine race now is not a race out of the lab. It’s a race to the patient,” he says. And the most successful vaccines, Townley says, will be those made by the companies that pay the most attention to the last mile of the race.

That last mile — the vaccine’s journey from, say, centralized distribution centers to clinics and finally to patients — isn’t a measure of distance. It’s a pothole-strewn maze of regulations and supply chains that companies must navigate to get their vaccine distributed, eventually to almost every person on the planet.

The magnitude and intensity of the task ahead is unprecedented, Townley says. “It is the largest product launch in the history of humankind.”

Managing the last mile

The sheer scale of vaccinating the world is daunting. With most COVID-19 vaccines in development requiring two doses for full effect, there will be a need for roughly 15 billion doses globally.

Management of the vaccine rollout is a key variable — at least as important as vaccine efficacy — in the equation determining how well a vaccine will quell the pandemic, researchers reported November 19 in Health Affairs. Researchers considered different scenarios, figuring in vaccine effectiveness, the pace at which people could be vaccinated (depending both on delivery systems and public willingness) and how quickly the virus spreads.

Even a vaccine that is only 50 percent effective in preventing disease could quell the pandemic if it were distributed quickly enough, says study coauthor Jason Schwartz, a vaccination policy researcher at the Yale School of Public Health. “Implementation matters.”

Creating the vaccines is a remarkable scientific achievement, Schwartz says, but the technical and logistical challenges of getting the vaccines where they need to go is going to be every bit as challenging as the scientific issues.

For example, while many of the vaccines in the works will require refrigeration, Pfizer’s vaccine — the first fully tested vaccine to get permission for emergency use — must be kept especially cold, frozen at –70° Celsius. That vaccine requires ultracold freezers or dry ice for refilling specialized delivery containers (SN: 11/20/20). Moderna’s vaccine also needs to be frozen, but is stable at regular freezer temperatures.

To get a sense of the task ahead, imagine “putting two iPhones in the hands of every single human on the planet, and make sure those iPhones are cold when they get there,” Townley says.

Refrigerated and freezer trucks, planes and trains that can transport such chilly goods aren’t in huge supply. Cold transportation is also necessary to move bacon, avocados and many other foods and medicines, such as insulin, Townley says. “Normal systems are not built to take on this large of a challenge in this short of a time frame,” he adds.

As a result, trade-offs will need to be made. Either distributors won’t be able to ship some other temperature-controlled cargoes, or they will need to add more cold-shipping capacity, which is expensive.

Much of the need for cold shipping is seasonal, such as avocado season in South Africa and Mexico. ”If the vaccine season hits South Africa at the same time as avocado season [and] there’s not a whole lot of capacity for carrying avocados,” Townley says, “what does that do to South Africa’s economy?”

It will be hard enough for many places within the United States to manage Pfizer’s super-cold vaccine, says Mei Mei Hu, cofounder and cochief executive of Covaxx, a company based in Hauppauge, N.Y., that is working on its own COVID-19 vaccine. And “if it’s difficult in the U.S., it’s going to be virtually impossible in most emerging markets,” such as Central and South America and many places in Africa, she says.

Even regular freezers, such as those needed to store Moderna’s vaccine, may be a challenge in some areas. “There’s lots of places where you can’t get a cold Coke,” Hu says.

Keeping it cold

Pfizer has devised special shipping containers, nicknamed pizza boxes for the food delivery containers that they resemble, that can be recharged with dry ice to keep the company’s vaccine cold in transit and for short-term storage. The U.S. government has told states that it will send one dry ice recharge with each shipment of the vaccine, says Kurt Seetoo, the immunization program manager for the Maryland Department of Health in Baltimore.

But that recharge won’t last long, so providers will need to find local sources of dry ice, which may be difficult in rural areas. Maryland is working with local contractors to ensure there will be a ready supply of dry ice when it is needed, Seetoo says.

Pfizer has assured health officials in the United States that its vaccine can be held for up to 15 days in its pizza boxes with dry ice recharges every five days and then spend another five days in the refrigerator before going bad, Seetoo says. That gives officials about 20 days to distribute the vaccine once they receive it.

Still, dry ice sublimates, or turns directly into carbon dioxide gas. The fumes can build up and suffocate people if there’s not enough ventilation, which could make transporting and storing vaccines cooled with dry ice a problem.

One solution is to use devices developed for transporting cells between laboratories or for moving temperature-sensitive medicines, such as those used in cancer or gene therapies, to clinics, says Dusty Tenney, chief executive of Stirling Ultracold, a company that makes portable freezers that go as low as –80° C.

Stirling’s portable freezers — which look like high-tech versions of beach coolers — are being deployed to get COVID-19 vaccines from “freezer farms,” where the vaccines are stored after they come off production lines, to clinics and other distribution sites.

Such freezers are just one link in a “cold chain” needed to keep the vaccines fresh and effective. But the chain is fragile. The World Health Organization estimates that about 2.8 million doses of vaccines were lost in five countries in 2011 because the cold chain was broken. That includes losses in countries such as Nigeria, where 41 percent of refrigerators were nonfunctional, and Ethiopia, which had about 30 percent of its cold-chain equipment go kaput. Losing millions of doses of COVID-19 vaccines could be disastrous for getting a handle on the pandemic.

Dosing dilemma

In the United States, another hurdle is that each state isn’t sure how much vaccine it will get from the federal government, Seetoo says. That makes it hard to determine how many doses the state will get for health care workers and people in long-term care homes who will be first in line to get the vaccine (SN:12/1/20).

And the two-dose requirement for most COVID-19 vaccines adds to the supply problems, says Christine Turley, a pediatrician and Vice Chair of Research for Atrium Health Levine Children’s Hospital in Charlotte, N.C. Unless doctors, pharmacies and other providers are sure they’ll have a steady supply of vaccine, they will need to save half of a shipment to give people booster shots three weeks to a month after the first shot.

“If I vaccinate people and can’t provide a second dose, that’s not meeting a moral and ethical obligation,” Turley says.

Keeping track of who got vaccinated, which vaccine they got — both doses need to come from the same company — and when people are due for a second dose is another potentially daunting logistical challenge. Databases used to manage patient data or to order and ship medical supplies aren’t well integrated among vaccine providers and local, state and federal government agencies, which could lead to confusion, says Pouria Sanae, chief executive of ixlayer, a company that provides logistics services for COVID-19 testing and vaccination centers. Existing databases may need to be beefed up and given new ways of managing information, he says.

And it’s not just digital infrastructure that will be important. Physical spaces will be needed to administer the vaccines and their multiple doses to many, many people as quickly and efficiently as possible.

For comparison, Sanae points out that the demand for widespread COVID-19 testing initially took many people by surprise. “If we went back to January and I told you we’d be collecting testing samples in a parking lot, you’d probably laugh at me,” he says. But that’s what it may take to get vaccines distributed as widely as tests are. He envisions every school, government and community testing center converted to vaccination clinics, along with doctors’ offices, pharmacies, hospitals and other clinics.

Logistical nightmare

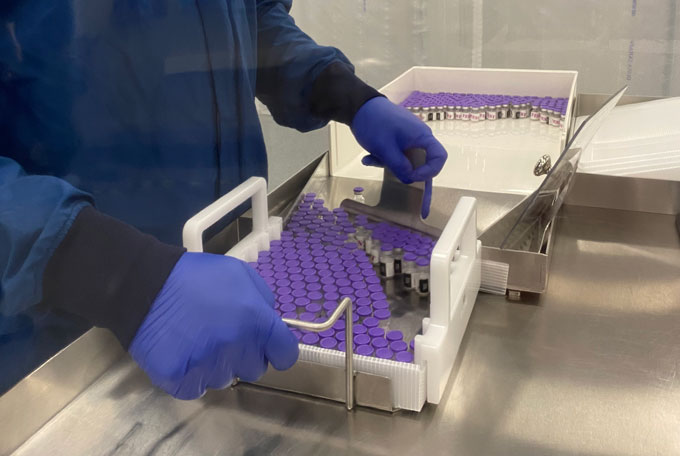

Finally, it’s not just the vaccines themselves that need to be rolled out smoothly. Suppliers of the glass vials that hold the vaccines have to make sure they have enough surgical-grade sand to make the vials. Nurses giving vaccine shots need alcohol wipes, syringes, needles, masks and gloves, some of which are in short supply in places. Managing all of those logistics is a sticky proposition, especially on the scale needed to immunize the world against COVID-19.

“The logistics just keep going,” Turley says. From Borneo to Paris to Charlotte, N.C., how best to distribute vaccines is a problem people are facing everywhere, she says. “The only consolation is that everybody is grappling with this, and that’s really no consolation to any of us.”

Even if everything goes smoothly and distribution happens as swiftly as the vaccines’ initial development, all could be for naught if people don’t take other measures, such as universal mask wearing and social distancing, that can help slow the spread of the virus.

Schwartz, the vaccination policy researcher at the Yale, and his colleagues took virus spread into account when making their calculations. If things keep going as they have in the past few weeks, with more than 150,000 new coronavirus cases and about 1,500 deaths — about one every minute — reported daily in the United States, vaccine distribution would need to move lightning fast to prevent millions more deaths. “If we’re at that [high level of transmission], even a highly effective vaccine will struggle to make a dent in the trajectory of the pandemic,” Schwartz says.

Three Truths to Address Sexual Exploitation, Abuse & Harassment in the UN

Three Truths to Address Sexual Exploitation, Abuse & Harassment in the UN  COP27 Fiddling as World Warms

COP27 Fiddling as World Warms  Somalia: Human rights chief decries steep rise in civilian casualties

Somalia: Human rights chief decries steep rise in civilian casualties  UN chief highlights crucial role of G20 in resolving global crises

UN chief highlights crucial role of G20 in resolving global crises  Ukraine: UN convoy delivers vital aid to residents of Kherson

Ukraine: UN convoy delivers vital aid to residents of Kherson  COP27: Week two opens with focus on water, women and more negotiations on ‘loss and damage’

COP27: Week two opens with focus on water, women and more negotiations on ‘loss and damage’  A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes  What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?

What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?  This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces

This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces  Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now

Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now