By now, most people have gotten the message that wearing a face mask is one way to help stop the spread of COVID-19. But now health officials are taking the masking message a step further: Don’t just wear a mask, wear it well.

Taking steps to improve the way medical masks fit can protect wearers from about 96 percent of the aerosol particles thought to spread the coronavirus, a study by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found. That’s provided both people are wearing masks. But even if only one person is wearing a mask tweaked to fit snugly, the wearer is protected from 64.5 percent to 83 percent of potentially virus-carrying particles, the researchers report February 10 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“I know some of you are both tired of hearing about masks, as well as tired of wearing them,” CDC director Rochelle Walensky said February 10 during a White House briefing. But scientists have learned in the past year how effective masks can be to protect people from catching COVID-19, she said. “The bottom line is this: Masks work, and they work best when they have a good fit and are worn correctly.”

That message is increasingly crucial as more transmissible coronavirus variants — including ones first detected in South Africa and the United Kingdom — are beginning to spread more widely in the United States (SN: 2/5/21).

Plenty of studies have already demonstrated that masks cut down on the amount of spit particles that may spray others when a person breathes, talks, coughs or sneezes (SN: 6/26/20). Still, photos and videos show that air and droplets often escape from the tops, sides and bottoms of ill-fitting masks. “Even a small gap can degrade the performance of your mask by 50 percent,” says Linsey Marr, an environmental engineer at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg.

Good masks have both good filtration and good fit, she says. “Good filtration removes as many particles as possible, and a good fit means that there are no leaks around the sides of your mask, where air — and viruses — can leak through.”

Several recent studies, have demonstrated that some pretty simple measures to improve fit also cut down aerosol emissions. Those measures include using ear savers, pantyhose or mask fitters, or putting a cloth mask over a medical mask.

Those studies showed that wearing a mask protects other people from what the wearer spews out. But John Brooks, an infectious diseases physician and the chief medical officer for the CDC’s COVID-19 emergency response, and colleagues wanted to know whether those tricks to make masks fit better had any effect on protecting the mask wearer.

So the researchers set up two manikins facing each other six feet apart. One manikin served as the source, “exhaling” via a tube aerosol particles of saltwater of a size that could carry the coronavirus. (No viruses were used in the experiment.) The other manikin was the receiver.

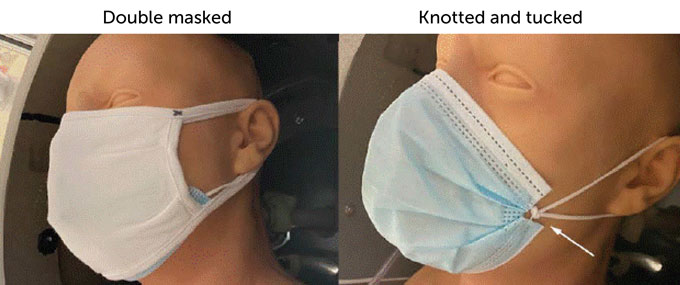

The researchers measured how many saline droplets reached a mouthpiece in the receiving manikin that represented its nose and throat. In some experiments, the team put medical masks on just one of the manikins. In others, both wore masks. The team tried two scenarios to make the mask fit better: knotting the ear loops close to the mask and tucking in the ends to eliminate side gaps; and wearing a cloth mask over the medical mask.

In each set-up, the result was compared with wearing no mask at all.

When the receiver wore an ill-fitting mask, the amount of droplets reaching its throat was reduced by 7.5 percent. When the source was the one wearing the mask, the receiver’s exposure was reduced by 41.3 percent. And when both dummies wore masks, particle exposure was 84.3 percent lower than with no mask.

That’s pretty good. But not as good as it could be. When the receiver wore a knotted and tucked mask, its exposure was reduced by 64.5 percent. And when both manikins wore the knotted and tucked masks, protection was even stronger: Exposure dropped by a whopping 95.9 percent.

Wearing a cloth mask over the medical mask improved fit even more. When just the receiving manikin wore the double mask, it was protected from 83 percent of particles. And when both manikins doubled up on masks, 96.4 percent of particles were blocked from reaching the receiver’s mouthpiece.

Those data show that “it’s mask fit that really matters, and there are bunch of different ways to improve mask fit,” says David Rothamer, a mechanical engineer at the University of Wisconsin–Madison College of Engineering.

Rothamer and colleagues tested devices called mask fitters or mask braces — rubber or plastic frames that fit over the mask molding it more closely to the face. A medical mask alone filters about 20 percent of aerosol droplets leaving the mouth, protecting others slightly. With a mask fitter in place, 90 to 95 percent of droplets were filtered, Rothamer and colleagues reported January 4 at medRxiv.org. That report hasn’t been reviewed by other scientists yet. The CDC team didn’t test mask fitters, but that level of filtration should help protect the wearer, too.

Piling on masks beyond two masks probably won’t improve filtration, and it may muffle voices and make it difficult to breathe, says Monica Gandhi, an infectious diseases doctor at the University of California, San Francisco. “No more than two. Just stop there, please.”

She and Marr proposed the double masking strategy to improve the fit of the medical mask in the Jan. 15 Med. Medical mask material is electrostatically charged, which may repel microbes, in addition to filtering particles. The cloth mask helps reduce gaps around the sides and top of the medical mask. Although the CDC study tested the cloth mask over the medical mask, Gandhi says the order may not matter.

Doubling up on cloth masks hasn’t been tested, but Gandhi says it’s probably not helpful. “I see no point. It may improve fit, but it doesn’t improve filtration.”

There are many simple ways to improve the fit of masks, says Emily Sickbert-Bennett, an epidemiologist and head of infection prevention at the University of North Carolina Medical Center in Chapel Hill. A pantyhose sleeve over a medical mask improved filtration to about 80 percent, she and her colleagues reported December 10 in JAMA Internal Medicine. A mask fitter made of rubber bands as well as devices known as ear guards or ear savers also performed well. In unpublished work, the researchers have also confirmed that putting a cloth mask over the medical mask works well.

Beyond the question of fit, the CDC report also illustrates how important it is for everyone to wear masks, Sickbert-Bennett says. “The best form of double masking is when you and the person you’re interacting with are both wearing a mask.”

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes

A new treatment could restore some mobility in people paralyzed by strokes  What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?

What has Perseverance found in two years on Mars?  This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces

This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces  Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now

Greta Thunberg’s new book urges the world to take climate action now  Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight

Glassy eyes may help young crustaceans hide from predators in plain sight  A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?

A chemical imbalance doesn’t explain depression. So what does?